May Move Out

April 25th 2013 to May 11, 2013

Sarah D’ Alexander, Reed Callahan, Sean Kinghorn

In the Spring of 2012, Geog 360 student, Sarah D’ Alexander embarked on a major campus donation drive known as the May Move Out. The purpose of this project was to collect many of the items students typically throw away at the end of the year and donate these items to local charities and the OWU Freestore. It was estimated that 43 tons of “waste” was donated and kept from the massive dumpsters set up all around campus. However, in the Spring of 2013 the two recycling coordinators (Reed Callahan & Sarah D’ Alexander) and the OWU sustainability coordinator at the time (Sean Kinghorn) revisited this project with a full vengeance for waste reduction. We examined the successes and failures from last years May Move Out and worked to improve the project. Many of these changes pertained to improved organization, systematic structural changes and increased signage and donation bins. All of these factors led to a significant increase in donations collected.

The May Move Out for Spring 2014 was modified in an attempt to have existing OWU staff complete the work, but with mixed results. A revival of the May Move Out, based on the experiences in 2012 and 2013, is planned for the spring of 2015. Contact John Krygier for more information.

Go to May Move Out Spring 2012 | Go to May Move Out Spring 2013

Note: Both the 2012 and the 2013 report have not been updated so some of the information is out of date.

May Move Out Spring 2013

Reed Callahan, Sean Kinghorn

In regards to the results of this year’s May Move Out we were not able to collect accurate empirical data on the amount of donations collected. Last year Sean was able to examine the differences in waste accumulation and reduction due to the May Move Out, and conduct a comparative analysis of waste tonnage diverted. He was able to conclude that when comparing a 5-year average of waste produced in the past years before the May Move Out that in the Spring of 2012 when the May Move Out was first implemented it diverted 43 tons of waste. The data for this years waste diversion from the May Move Out should be available around mid June, but there is no individual available to calculate the amount of waste diverted for the 2013 May Move Out. Krygier, this may possibly be a project you could do for a future student; have them collect the data from Waste Management, which is provided to the University and have them figure out the amount of waste diverted from this years May Move Out.

Planning the Event

While trying to restructure the May Move Out the most useful source we had was the experiences Sarah and Sean had from last year running the project. We started planning for the Spring 2013 May Move Out in the beginning of the Spring Semester, and this really helped us properly plan out the project and make the necessary contacts.

While planning for the May Move Out there was not a sequential order of steps we followed that led to the end product; we slowly developed upon a broad based plan and then dissected the specifics of each main part of the project. When designing the plan an important aspect was the scale of the project. We realized that we needed to not bite off more than we could chew, and make the May Move Out manageable for the amount of time and effort we would be willing to contribute to the project. This can be a very time consuming project and it is important to realize the lack of free time people have around that time in the semester. In this year’s May Move Out in the last week, Sarah Sean, and I were probably working 5-7 hours a day. If next years students are able to get more volunteers than it may be feasible for some individuals to not commit that amount of time, but this project really requires a few dedicated volunteers to make large time commitments.

When trying to evaluate the scale/size of the project we first needed to consider how many donation areas do we want to have around campus. Last year the donation areas were located in one spot in every dorm and there seemed to be a lack of consistency in the donation locations. This year we put donation boxes on every floor of every residence hall, and donation boxes in every fraternity house, senior housing and SLU.

Shown below is the list of all donation areas (floors for each residence hall and number of fraternities, SLUs, senior housing)

- Stuy: 3 floors (12 boxes)

- Smith West: 4 floors Smith East: 5 Floors (36 Boxes)

- Hayes: 4 floors (16 Boxes)

- Thompson: 3 floors (12 Boxes)

- Bashford: 4 floors (16 Boxes)

- Welch: 4 floors (16 Boxes)

- 9 Senior Housing and Fraternities (36 boxes)

- 7 SLUs (28 boxes)

Donation Box Layout

One question that may come to mind is why did I list the number of boxes after each location. This year we decided to use four donation boxes at each location. These four boxes each had labels indicating the types of items that should be placed in them.

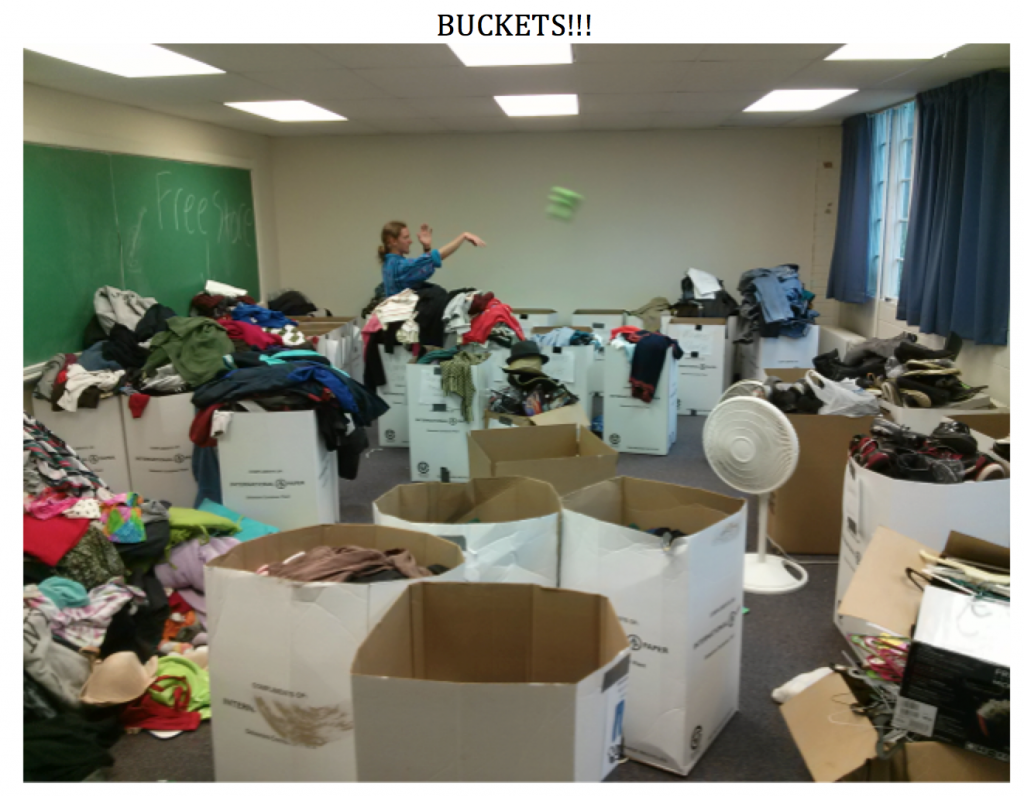

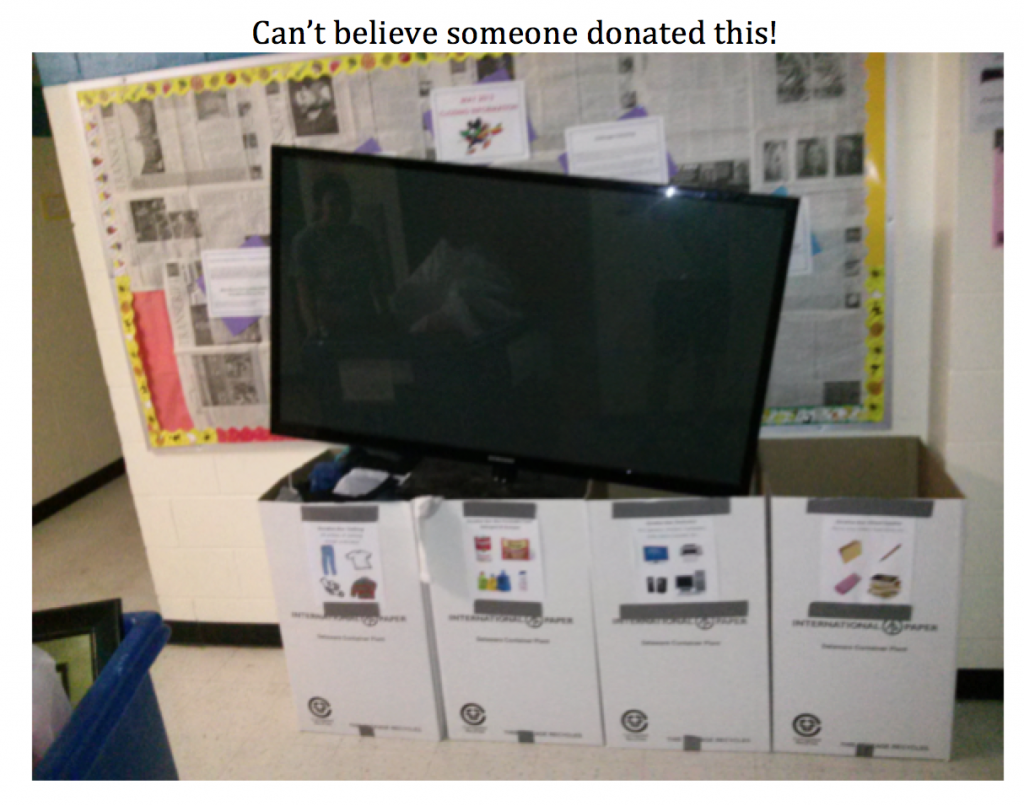

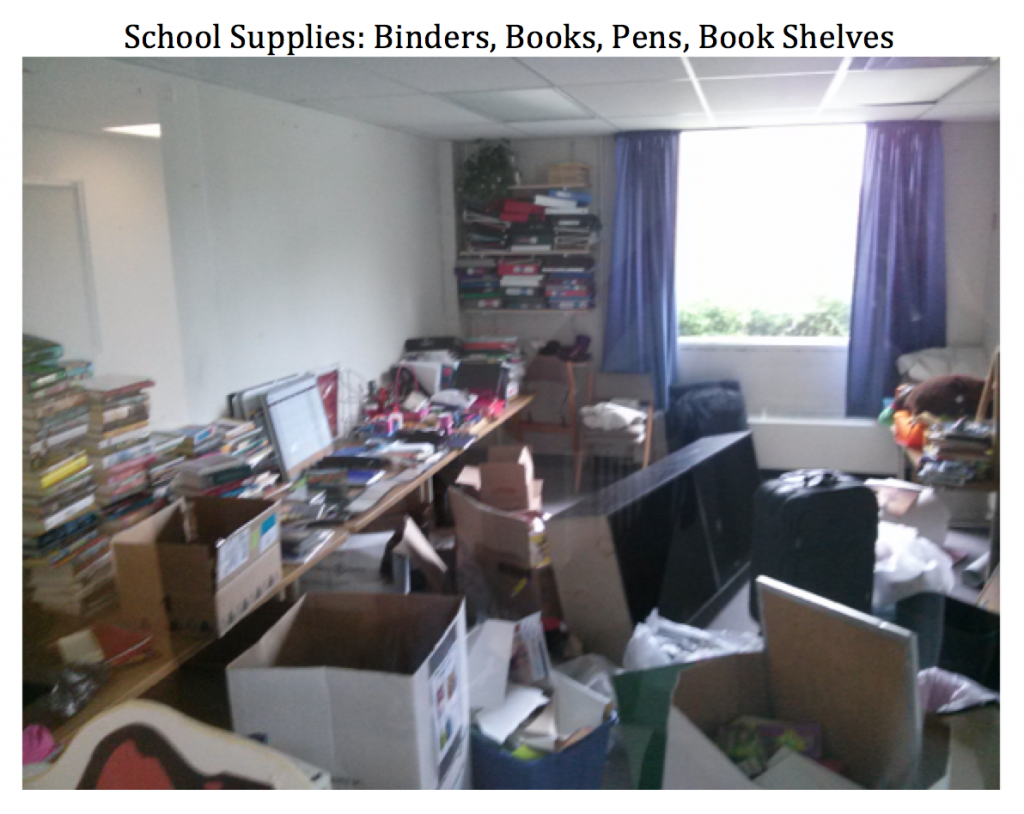

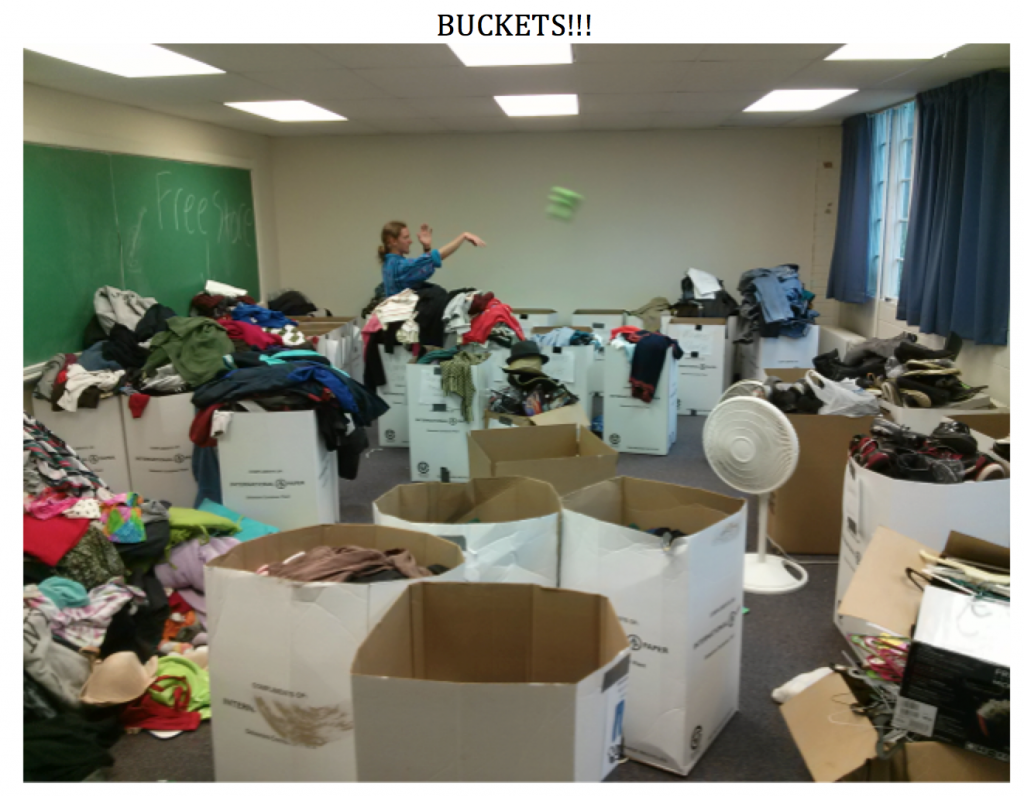

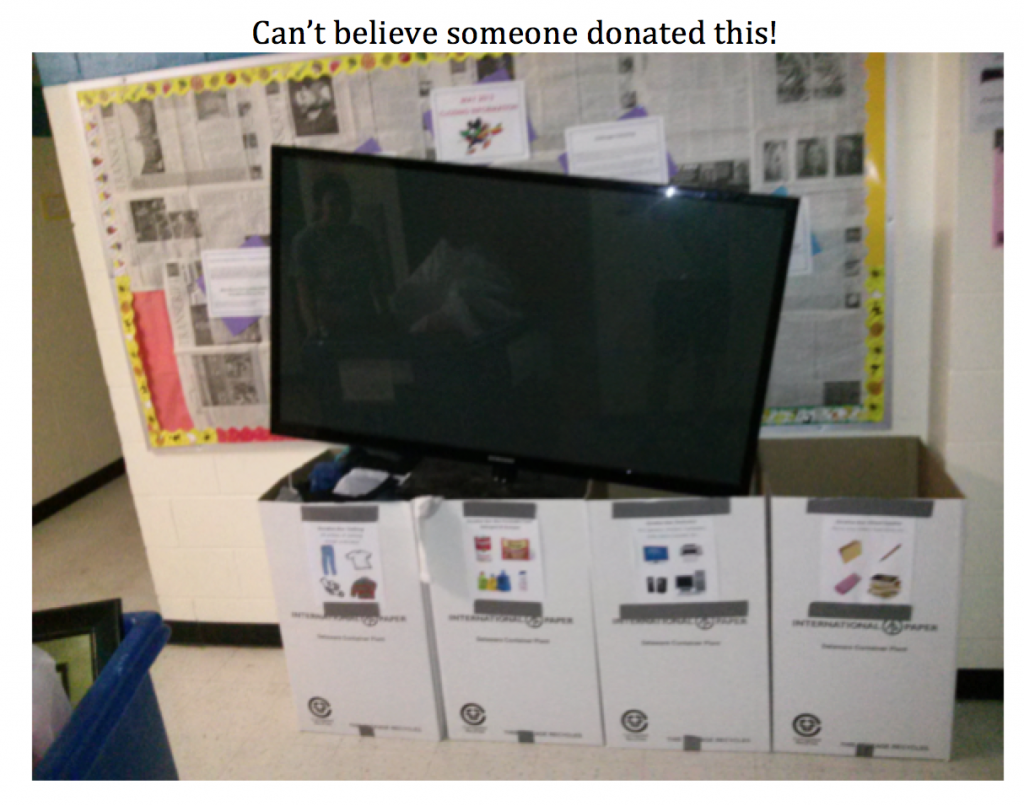

The four categories the bins were divided into were school supplies, non-perishable food items/detergents, clothing, and electronics. (I will send an email attached with the signage we used) This system of bin layout contributed to the students separating their items and when dividing the items in the OWU Free Store this saved a significant amount of time in the sorting process. The sorting of items in the May Move Out can be very monotonous so this relieved many of the volunteers from this type of work. As a result more volunteer’s time and effort could be allotted to donation collection. In regards to the decision to collect these types of items, the experience of the past May Move Out helped us gauge the types of items that students typically disposed of at the end of the year. Along with that, the signage used on the donation boxes was very simplistic and used a visual aid to help guide students to the proper bin for their donated items. As a result we had very little contamination or incorrect items in the various donation boxes.

Donation Box Locations

Another important feature of our donation locations was the centralized donation areas in each residence hall that was intended for larger items such as futons and mini fridges. Our reasoning behind the use of this location was that the four donation box areas were in the hallways and larger items being placed in the walkways could be a fire hazard or a more serious concern is that it could look aesthetically unpleasing. The centralized donation areas were typically on the first floor of the residence halls, where there was ramp access, but still easily accessible to students. We indicated the specific location of the centralized donation areas by taking a photo of the location and putting it on a sign that was placed above the donation boxes on each floor. (Refer to the attached pictures of the signage).

The scale of the project may have been double the size of last years May Move Out, but along with that we had to make sure Res Life approved of the project and the changes we planned to make around the residence halls. An important aspect to note for future groups is that constant communication with the RLC’s is crucial for this project. We met with the RlC’s multiple times and explained where we planned to have donation bin locations and the types of items we were collecting. In order to create as much transparency about the May Move Out to the RLC’s we set up a meeting and showed a PowerPoint of all the locations within the residence halls where the donation bins will be placed and exactly how they will look. This may have taken some extra time, but it worked well because the RLC’s were able to provide us with valuable advice and information that we never would have known. Also photo documenting the locations helped tremendously when we gathered volunteers to help distribute the donation bins all across campus and when donation collector knew exactly where to pick up the bins.

Here is the link to a PDF that shows all of the bin location we proposed to the RLC’s around campus (this document is available in Google Docs, please contact John Krygier for access).

Volunteer Recruiting

The May Move Out relies heavily on the use of volunteers for the success of the project. This year we tried our hardest to get as many volunteers as possible, but we still did not have the turn out we originally hoped for. It is obviously a difficult time in the semester to ask students to commit a few hour volunteering when they have a big final, paper and/or project due that week. We tried to reach out to as many students as possible, but also faculty and staff. Many individuals in the University’s administration or even professors may have some free time to help out and it is worth reaching out to them. This year we had a few professors and even Chaplain Powers and his staff show up to volunteer and that honestly made a huge difference for the success of the project.

List of strategies/methods used to recruit volunteers

- OWU Daily: we started submitting OWU Daily’s a month before the first week of the May Move Out, but no one responded. We then changed the message in the OWU Daily to “Want Free Stuff” and then explained if students volunteer for the May Move Out they get first dibs on the items we collect. We also had a link to our volunteer sign up sheet.

- The Transcript: get a reported from the Transcript to write a piece about the project. No one really reads the Transcript, but it can’t hurt

- Service Learning Hours or Probation Hours: Some classes/majors or organizations require a certain amount of Service Learning hours so let the school administration know about the project and that you need volunteers so students can be directed towards your cause. Also when students get in trouble they need to get a certain amount of community service hours.

- Word of Mouth: This was probably the most valuable way to recruit people and often allowed us to guilt individuals into volunteering. Also reach out to certain clubs or organizations that typically do a lot of service work (Progress OWU, Environment and Wildlife Club, etc.)

Volunteer List

One of the greatest successes of this year’s May Move Out was the volunteer list we created. There were three different volunteer positions that individuals could sign up for, and we allotted the number of volunteer slots and times based upon our speculated number of volunteers needed on each day. Our approach is documented in the May Move Out Volunteer List (.xlsx file). A Google Docs version of this file is available from John Krygier).

List of Volunteer Positions and Descriptions

The description of these positions helps shows how we intended these volunteer positions to interact within our donation collection and sorting system

Donation Monitor Volunteer Description:

Your job as Donation Monitor will be to do a walkthrough of your assigned residence hall on the day you have signed up. You will need to go and check the various donation locations and call or text one of the van drivers if you notice a full donation box or a large item in the centralized donation area. This job only requires a short time commitment and can be done at your availability anytime before 4pm.

Donation Collector Volunteer Description:

The donation collectors will be helping us pickup donations at the various residence halls, SLU’s and fraternities. These individuals will be helping to move the donated items from the donation locations in the residence halls to the vans. The donated items will then be delivered to the OWU Free Store for sorting and further distribution to charities such as Goodwill & Habitat for Humanity.

Free Store Sorter Volunteer Description:

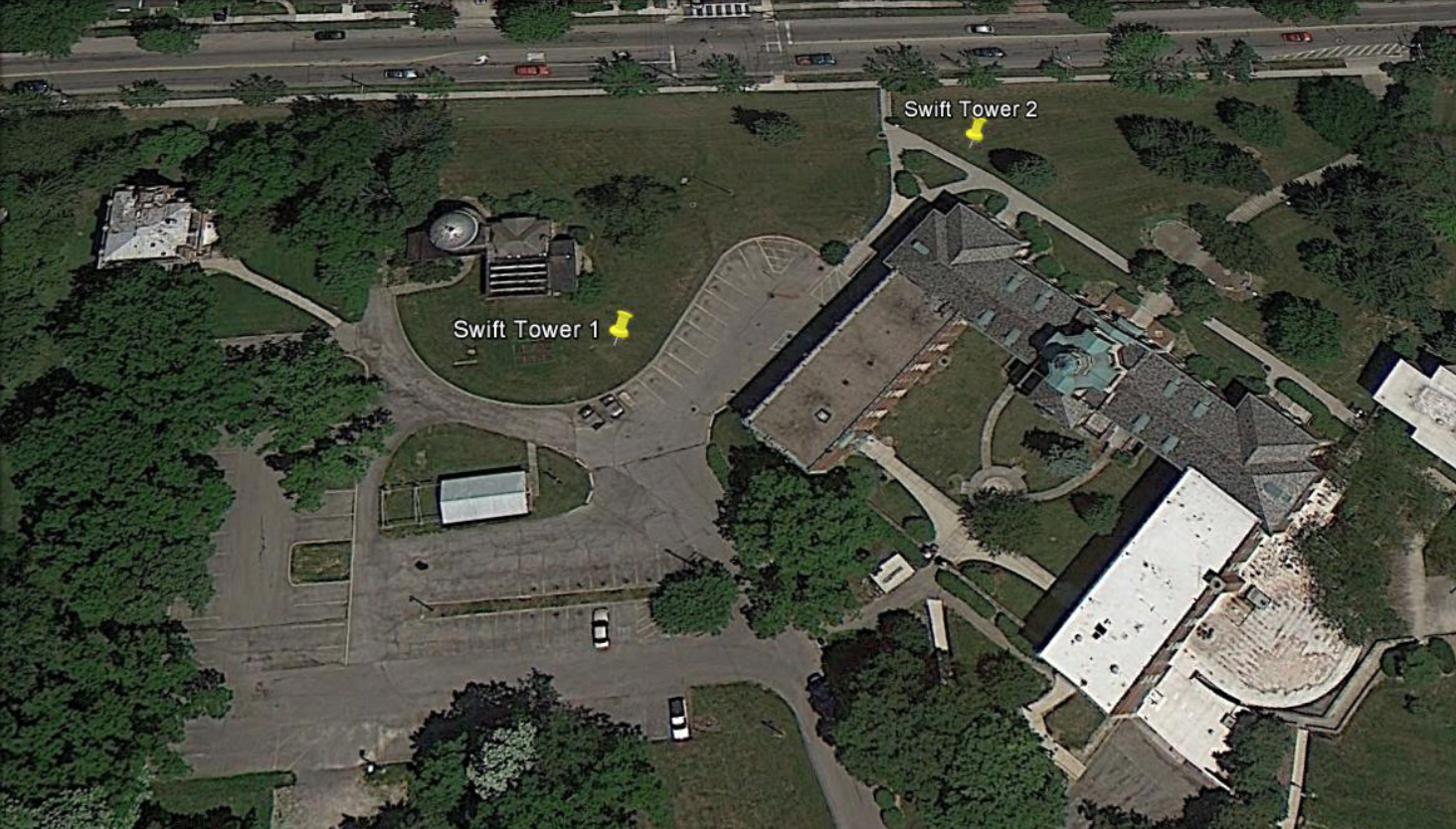

Your job will be to sort the donations delivered to the OWU Free Store. This job involves the seperation of donated goods into predetermined categories (clothes, electronics, school supplies etc.) as well as deciding which items should be left for the OWU Free Store and which items will be given to the other participating charities. We will provide more specific instruction upon your arrival. Free Store sorting will take place in the Stewart Annex, which is next to the jaywalk: 70 S. Sandusky St.

Another important part of the volunteer list was collecting the volunteers contact information, residency, and whether an individual was OWU van certified. We used this information to send out a reminder email a day before an individual’s volunteer shift to make sure they were aware of their commitment. Along with that we had people’s phone numbers to call them in case they missed a shift or if there was a change of plans that day. The information about volunteer’s residency was important because if we were having any problems in a certain dorm or needed some quick help we could reach out to individuals in that dorm or housing unit.

The May Move Out was only two weeks long (last two weeks of spring semester), but regardless of the amount of volunteers helping out the last week will be extremely hectic.

Our donation boxes on every floor of every dorm were filling up as fast as we could empty them and this caused non-stop donation collection all day, especially the Wednesday, Thursday and Friday of finals week. We had two OWU vans reserved all day for the entirety of those two weeks and having the vans is crucial. If future students are to tackle the May Move Out next year than they need to reserve at least two OWU vans and ask to have all of the seats taken out, except driver and passenger seats (felt like that disclaimer was necessary). If next years May Move Out Musketeers are able to recruit more volunteers than three vans may be necessary to avoid a bottleneck in time due to a lack of van accessibility.

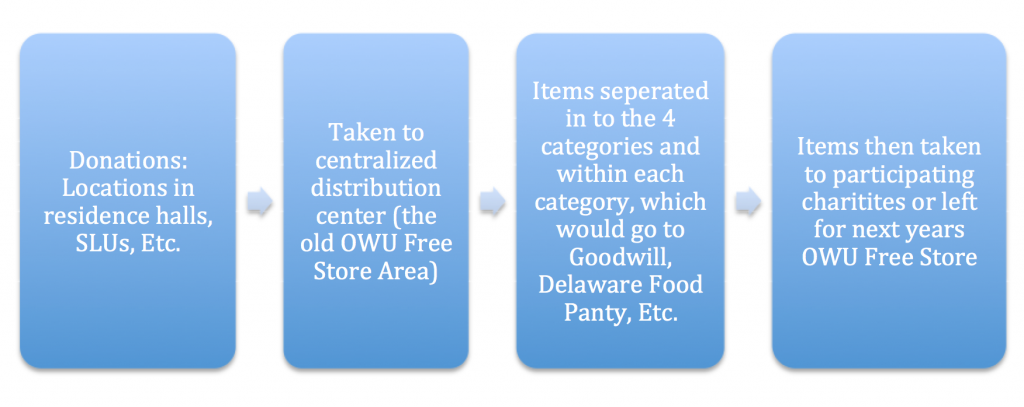

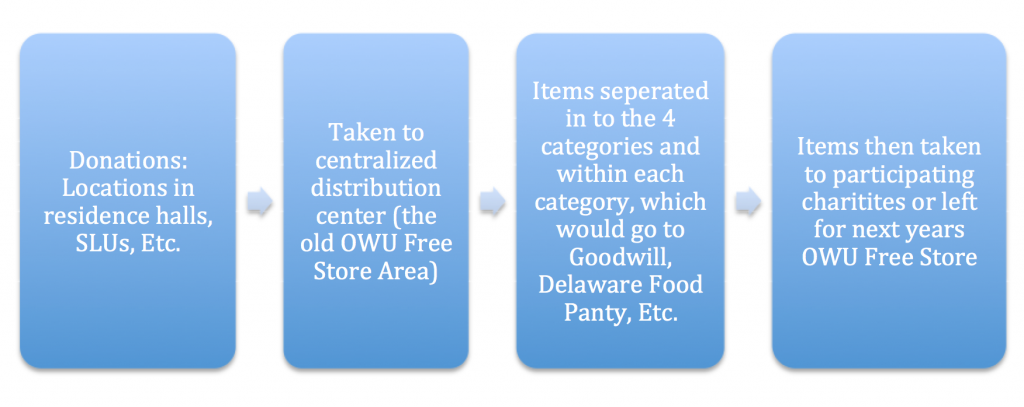

Shown below is the inflow and outflow of donations from the donation boxes, to the centralized distribution location and ultimately to end destination of these donations.

Sorting Process in the OWU Free store

The OWU Frees store, which is the Stewart Annex by the Ross Art Museum, was used as our donation distribution center. The Stewart Annex is a mostly vacant building that is still used by some faculty on the 2nd floor, but we used the first 3 rooms closest to the buildings entrance. These rooms stored the various items we collected and also helped us separate and categorize the donated items. Future students must make sure in advance that these rooms will be available in those two weeks and also all summer (items need to be stored there for next year’s OWU Free store). The school administration may put up a small fight for these rooms, but their reasoning behind denying you these rooms has very little valor; a group of alumni use one of those rooms once a year in the summer. If they make this point tell them that the rooms have been used for this project in the past two years, and that the rooms are so disgusting as it is that they should be ashamed for allowing alumni to step foot in those rooms. Often if you reason through the argument of aesthetics and alumni enjoyment then you can attack the heart of the beast known as the OWU administration.

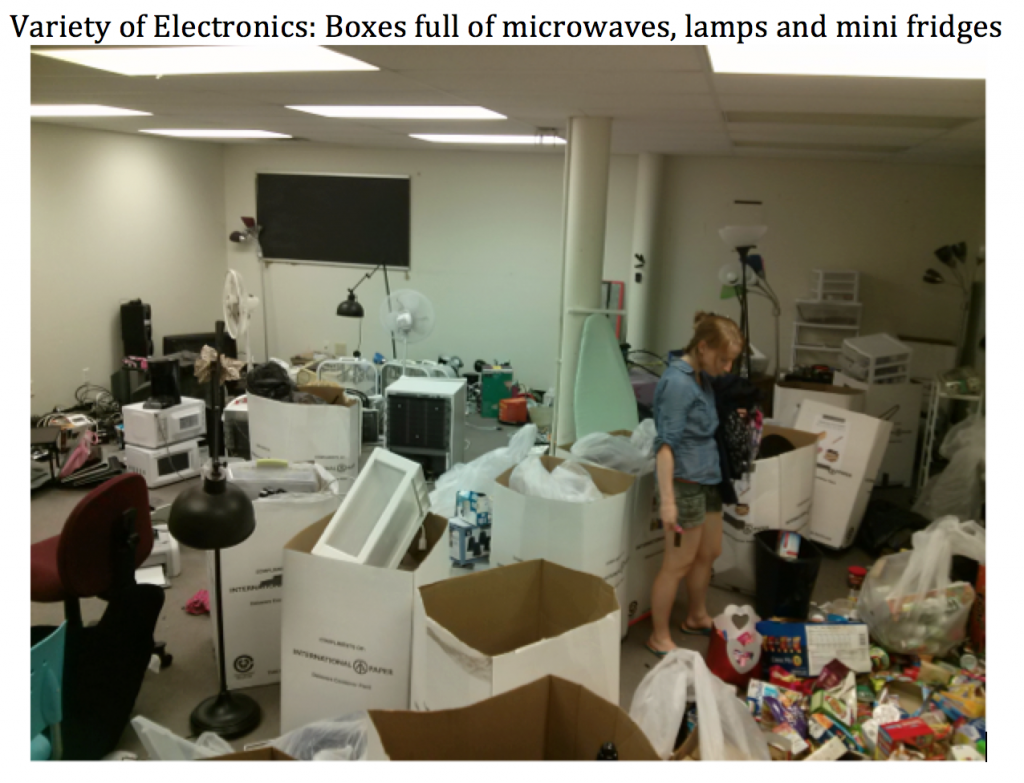

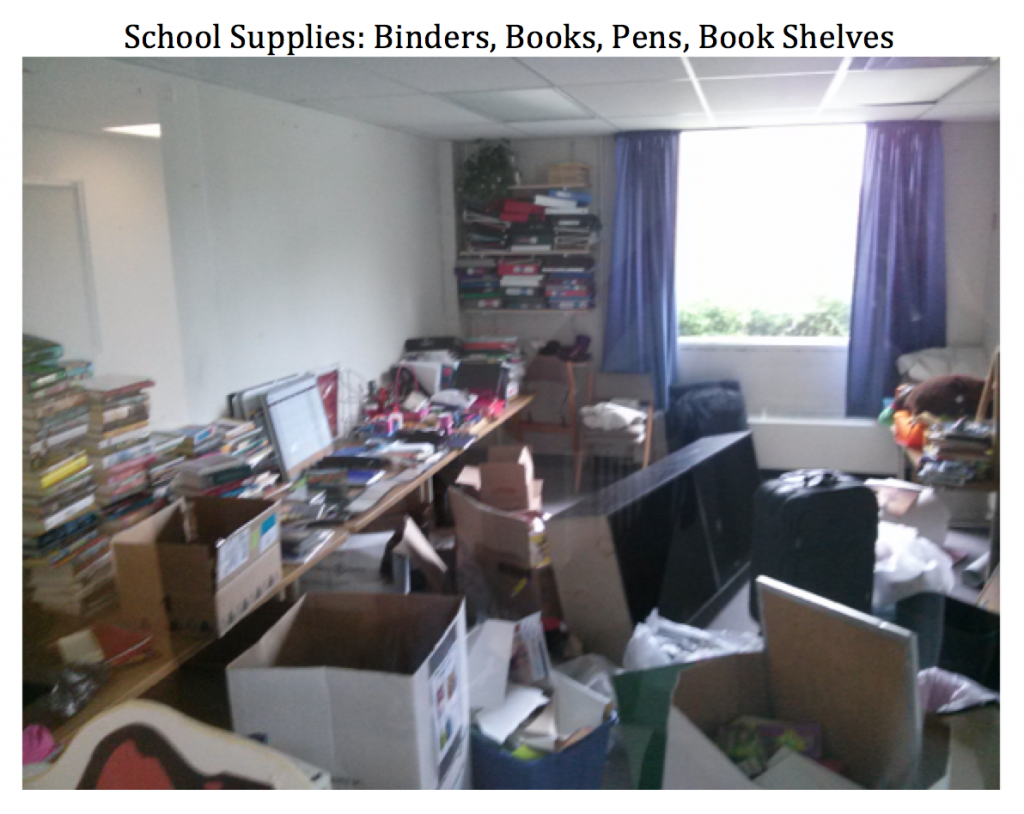

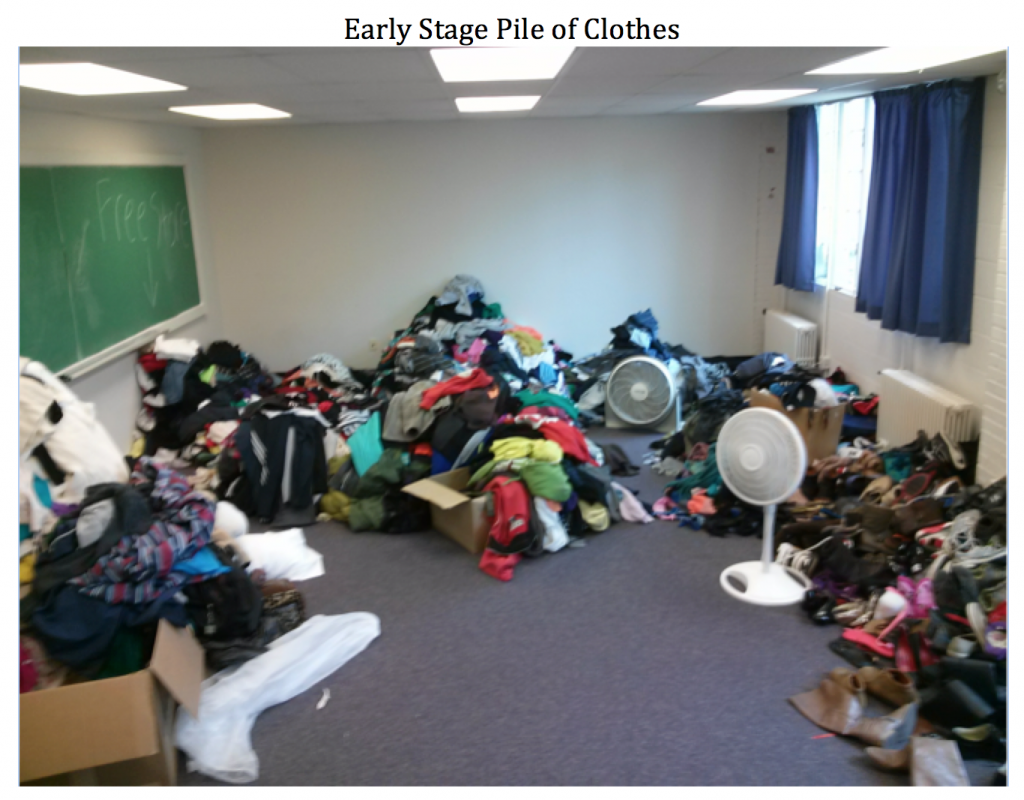

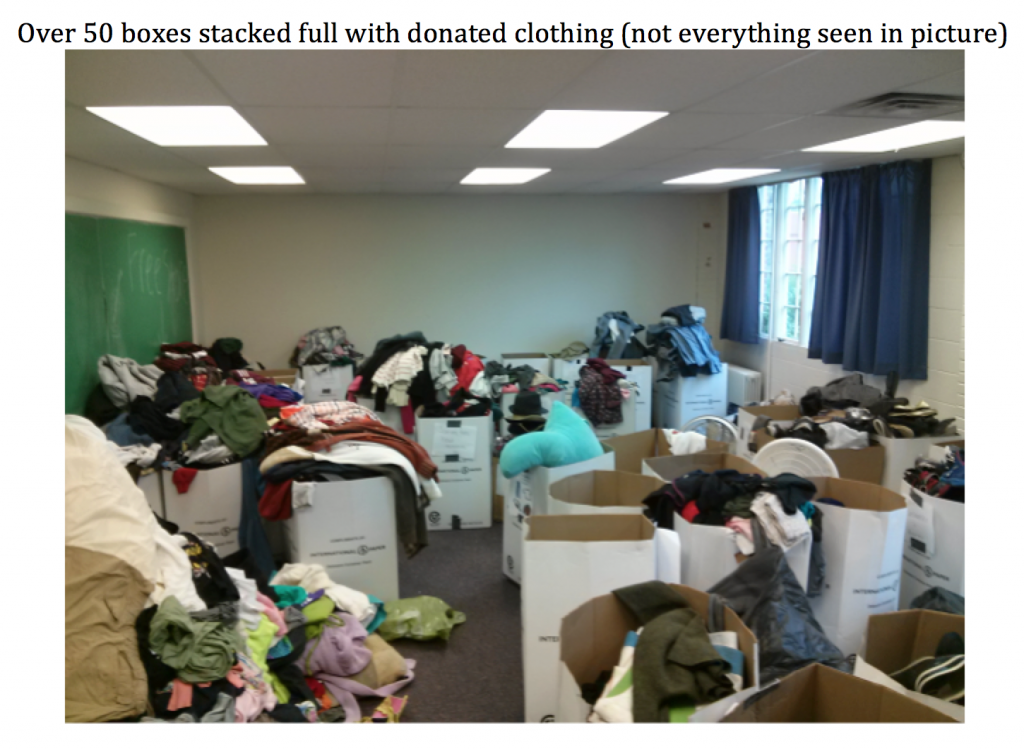

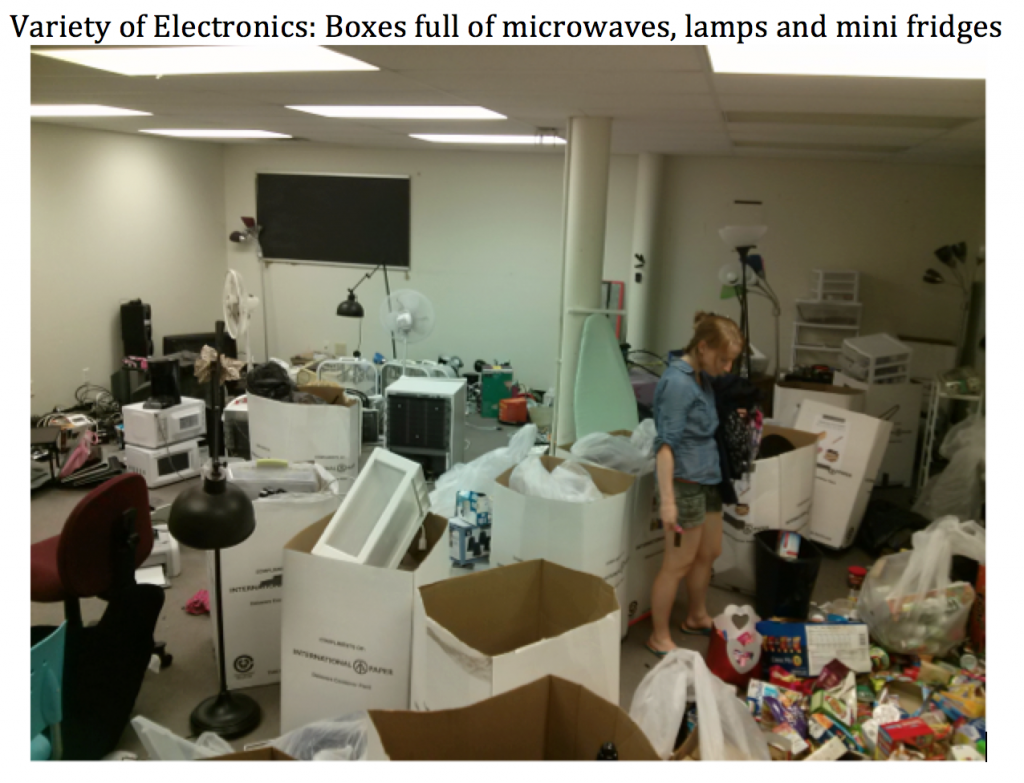

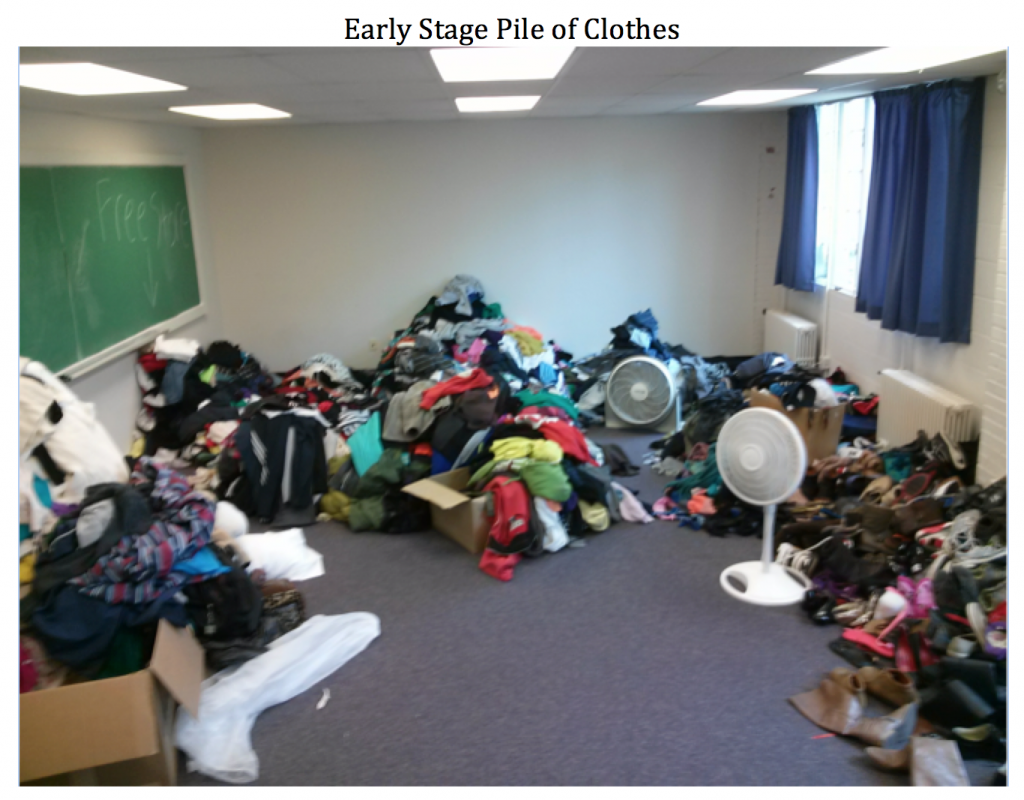

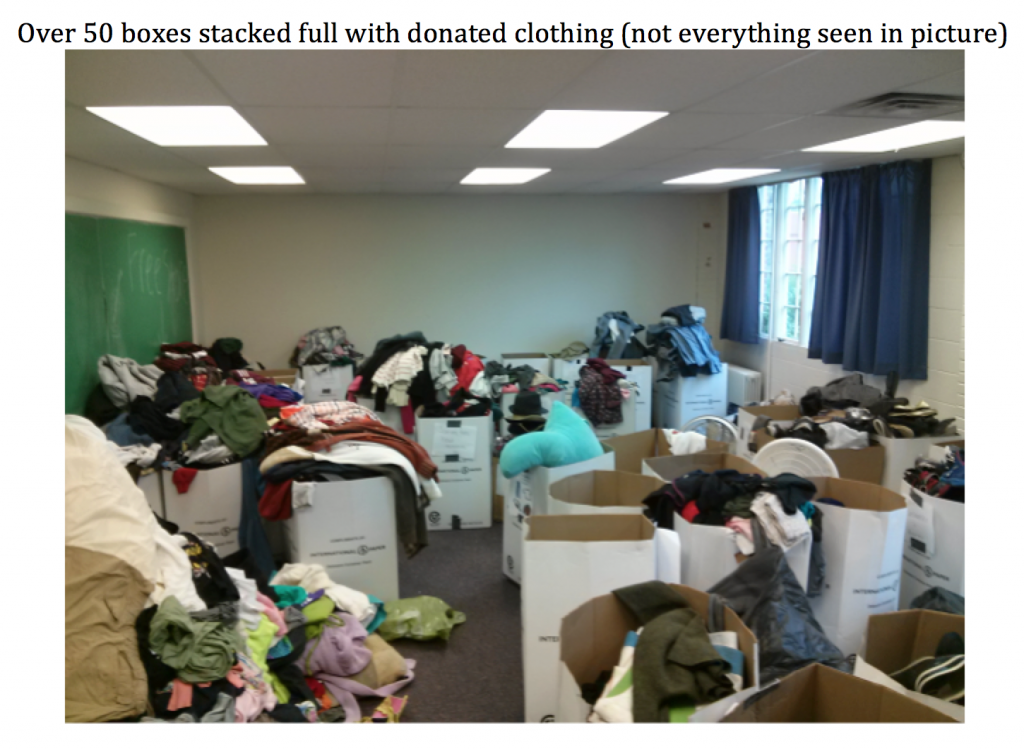

Shown Below is a variety of pictures we captured from the project and the layout of the different rooms in the Stewart Annex.

Recommendations/Advice

Learn from our mistakes. I advice all future group that want to take on the May Move Out project to learn from the successes and failures of the past two years of May Move Out’s and improve the project. Please fell free to use any of our signage (Download zipped file of signs here) Google Doc Spreadsheets (previously linked, here), or presentations that we used this year. Also understand that there are many improvements that could be made to our signage, Google Docs, donation bin layouts, etc. and alter these aspects of the project in a way that you see fit best.

The donation boxes we used were given to the school by the International Paper Company; make sure you have over 200 of these boxes at your disposal. OWU typically uses these boxes during large events or graduation when they need easily accessible trash bins, but they should have extras. Contact Building and Grounds in advance about the number of boxes you will need and establish a good relationship with someone in B&G, they can be a huge help for this project when it comes to needing supplies.

Try to recruit as many volunteers as possible. The success of the May Move Out project relies heavily on volunteer participation. The last two weeks of the semester is a difficult time for students, but try to get early commitment from individuals. Also reach out to University administration and faculty; they often have the ability to convince/force students and/or staff to help out. Reach out to the Delaware community for participation. Individuals from the Delaware community expressed interest in helping out this year, but we never had time to follow through with them. At the end of the semester some individuals from the Delaware go through the OWU dumpsters and collect items for charities so there is definitely interest within the community for this type of project.

Make sure you keep strong communication with Res Life and be transparent about exactly what you plan to do. Try to also get more involvement with Res Life physically helping out with the Move Out considering this project overlaps with many of Res Life’s job duties. We had originally asked that the RA’s be more involved with the May Move Out because it pertains to proper room check out and disposal, but we received very little help from the RA’s. My advice is to be really persistent with the RLC’s in getting the RA’s to be involved with the May Move Out. The RA’s do not have to be physically collecting donations, but they should be notifying volunteers when the boxes are full or helping advertise for the event. The RLC’s may tell you that the RA’s already have a lot on their plate and this would be too much extra work; they are lying. You would most likely be asking for a small time commitment and it would fall within their job description of managing the room check out process.

Advertise as much as you can. There are mixed feelings about the best way to advertise around OWU’s campus, but hitting all the different avenues can’t hurt. However, in the grand scheme of the project and regarding time management, this should be a fairly small portion. The bins in each resident halls are pretty self explanatory so students often know the boxes are for donations, but the advertisements around campus could explain the project and also see if students would be interested in volunteering.

Note: The document below describes the first May Move Out, modified for the second May Move Out in 2013, as described above. As with the 2013 report, this report has not been updated so some of the information is out of date.

May Move Out Spring 2012

Sarah D’Alexander, Sean Kinghorn

The Problem

Every year at the end of the spring semester, the strategically placed dumpsters all over campus become completely full and have to be emptied several times during move out week. This would not be such an issue if the dumpsters were full of garbage. However, upon closer inspection, one can find: printers, furniture, clothing, books, lamps, chairs and a wide variety of other reusable things that do not belong in a landfill. This is due to the fact that many students don’t have the time or the ability to transport all of their things back home in the rush of moving out, so they choose the path of least resistance —throwing it away.

We wanted to change this. Colleges all over the United States have dorm move out programs, and we wanted Ohio Wesleyan to be included in this demographic. Our mission was to make donating reusable furniture, school supplies, etc. to be as effortless as throwing them away. This way students would, by default, donate their extra things instead of throwing them into the dumpster. This is not only important for its environmental implications, but it would also economically benefit the university to not have to hire a truck to come empty the dumpsters so many times.

Our overall goals for this project were to:

- Reduce the amount of solid waste students produced

- Enforce the reuse of unwanted things

- Increase awareness on the importance of donating unwanted items

- To support the OWU Free Store which will be an active resource for the students on campus by the fall semester of 2012.

- Create a program that is continued every year

Project Setup

Organizing this project was a very large task because in order for it to be successful we needed as many people on campus as possible to be aware of our efforts. We also knew that we were going to need a lot of help! Upon researching what other schools had done we formulated a “to-do” list. We first had to plan the time-line for the project, so we could make sure that we could get everything done in a timely manner. To do this we worked extensively with Sean Kinghorn, the University’s Sustainability Coordinator, to help him organize and run the project. We also contacted Residential Life and Building and Grounds on campus, so they would be aware of what we wanted to accomplish and to get their cooperation and support. We wanted to collect a variety of things, so we created a donation list that we could hang with the donation bins, so students knew what they could drop off.

Next, we had to recruit volunteers. We did this by advertising our project and our need for student help in any way we could. We posted advertisements in the OWU Daily, created a facebook event where we could keep interested people updated on our progress, put up fliers, and contacted organizations on campus who could help provide volunteers such as: E&W, Circle K, Progress OWU and WCSA.

We tried to get a volunteer representative from each SLU, Fraternity and dorm on campus. This way we could make sure that we had a representative at every donation location that could be available to answer questions, help put up fliers, and let us know when donation bins needed to be emptied. We communicated with volunteers through email and through group meetings where we discussed the logistics of the project.

Gathering Resources

Nearly all of the resources we needed for the project, were donated, borrowed or already owned by the University. Goodwill donated large blue bins with wheels, which we put in each dorm to help move the donations. We also had several dozen large cardboard boxes donated to the university, which we put in each dorm for people to drop off clothing, non-perishable food, and small personal items. Buildings and grounds, while cleaning out storage units, came upon a couple of dozen small hard plastic recycling bins, which we put in the public bathrooms and laundry rooms for people to donate their left-over detergent, shampoo, soap etc. to local charities. All the other cardboard boxes we needed were given to us by the Thompson store.

Day of the Event

This event lasted about two weeks long, as we started receiving donations two weeks before the end of the school year. However, the majority of the donations came during finals week, when people began moving out. Sean Kinghorn and all available volunteers went around to each dorm every day to empty the donation boxes.

We sorted the donations into two piles: one that would go to a charitable organization and one that would go back to the students through the OWU Free Store. Due to our limited space we only accepted appliances, electronics, like-new clothing, and school supplies for the OWU Free Store. We kept these donations in a room at the OWU Annex, next to the Ross Art Museum, to be sorted through and organized.

The busiest days for collecting donations were the last day two days of finals (the Thursday and the Friday the majority of students had to move out by). We had so many donations that it took all morning and afternoon to get through all of the dorms, which we had to return to multiple times a day, since students were constantly dropping off unwanted things during the day.

Also, on the Saturday before finals week, we had the Habitat for Humanity Restore truck on campus all afternoon to collect larger items, such as furniture and appliances. This was especially useful this year because, due to a change in policy, the Fraternity Houses had to get rid of all of the furniture in their houses and the SLUs had to empty their storage rooms. We also had volunteers stationed at the truck to collect clothing or other donations that the Restore truck does not collect.

Results

By the end of the move out, we had collected an astonishing amount of items. A rough calculation determined that there were about 230 boxes donated to Goodwill (11,500 pounds); 2,000 pounds of furniture donated to the Habitat for Humanity Restore, 750 pounds of clothing and linens donated to the Community Free Store, and 70 boxes of donations went to the OWU Free Store (5,250 pounds). This resulted in a net weight of approximately 19,500 pounds of donations (nearly 10 tons!!!)

Also, the dumpsters themselves were emptied much less often than they had been in past years. For example, the large dumpsters behind Smith were emptied for the first time at about noon on the Friday after finals week, when ordinarily they would have already been emptied twice by then.

Tips

Since this was the first time a project like this had been attempted, there were a number of things that we could have done better.

- This is a large project so make sure you have at least two committed students heading the efforts along with a staff or faculty advisor

- Although we had been prepping and discussing the project all semester, we really didn’t start putting boxes out and meeting with the volunteers until mid-April. In the future, it would be better to devise a solid schedule ahead of time. This will make sure you stay on task, keep the volunteers notified on what is going on, and make sure there is a pick-up schedule for all of dorms.

- Getting committed volunteers was also a problem for us. Although we had been gathering volunteers since March, and we had about 30 responses, barely any of them actually showed up to help on the Thursday or Friday pick-up days. We did, however, have a few committed volunteers in each dorm who really helped us put fliers up and kept us updated on the status of the donations in their dorm.

- We only had one volunteer meeting to discuss the logistics of the project and, although there was a good turn out, not all of the volunteers could attend. In the future, having a volunteer meeting every couple of weeks would be beneficial; this will help commit the volunteers to the project. During this time you can devise a schedule to make sure you have volunteers each day of the move out week, and assign duties to each volunteer to make sure everything gets done.

- Even though we had an overwhelming number of donations there were still a number of residences where we did not actively collect donations. We did not have any volunteers from the Williams Drive Residences (4, 23, or 35) and we could not set up boxes there ourselves because only people living in those dorms have access inside. Also, we had participation from only a few SLUs (Tree House, Cow House, House of Thought and the Modern Foreign Language House) we did not have representatives from the other SLUs, so we could not effectively collect donations there. We had a similar problem with the Fraternities where we only had active participation from a couple of them (Alpha Sig and Phi Delt).

- We only had one van that we used to pick up things from each dorm. This made the pick-ups quite slow, since the van had to take a load to Goodwill or the OWU Free Store after nearly ever dorm. Hiring or getting a volunteer to drive another van would be a huge help in the future.

- It would have been helpful to have the support of other campus organizations as well. Nearly all of the help we did receive was from members of the Tree House and the Environment and Wildlife Club. It would be beneficial to contact as many organizations as possible, since they already have a group of committed students who could likely help. Organizations to consider are: SLUs, Circle K, Progress OWU, fraternities, sororities, WCSA, and members of ResLife.

When inspecting the dumpsters they contained no visible reusable items, which was a huge accomplishment. However, we did see a lot of recyclable things thrown away. There were more bags of plastic bottles, cans, and cardboard boxes than there was garbage! To take this project one step further in the future, it would be worthwhile to come up with a way to divert the amount of recyclable things thrown away. This could be done by emphasizing what can be recycled, communicating more effectively with buildings and grounds, and putting volunteers on “dumpster duty” to monitor what is going into the dumpsters.

Woodrow (Woody) Clark is an OWU alumnus (’67) long involved with environmental and sustainability efforts. The second edition of his Sustainable Cities and Communities Design Handbook (December 2017 info here and here) contains a chapter written by OWU student Emily Howald (OWU, ’18) and Professor of Geography John Krygier.

Woodrow (Woody) Clark is an OWU alumnus (’67) long involved with environmental and sustainability efforts. The second edition of his Sustainable Cities and Communities Design Handbook (December 2017 info here and here) contains a chapter written by OWU student Emily Howald (OWU, ’18) and Professor of Geography John Krygier.