A very cool project, planned and developed since 2012, is funded and ready to build. It has been delayed over and over, and frikkin’ COVID has slowed it down, but the plan is to start construction before the end of August (2021).

Watch for updates here: but for now, the proposal and details are below.

Proposal: OWU Chimney Swift Tower

Ohio Wesleyan University

Spring 2021

Dick Tuttle (’73), Caitlyn Buzza (’12), Alex Johnson (’15), Ashley Tims (’17), Dustin Reichard (Zoology), John Krygier (E&S, Geography)

Contact: John Krygier (jbkrygier@owu.edu)

Summary

The purpose of the Chimney Swift Tower project is to provide a safe area for resting and nesting of chimney swifts. Chimney swifts consume a significant number of mosquitos and thus reduce student’s exposure to mosquito-borne illnesses. The tower will also serve as an important point of interest on the residential side of campus, an attraction for both prospective students and those already on campus. As a student-driven project in collaboration with OWU alumni, the tower serves as a notable example of theory-into-practice and the OWU Connection.

Chimney swifts evolved to live in dead, hollow, tree trunks and adapted to chimneys over time. Chimneys are increasingly rare in new buildings and often closed off in older buildings. Thus humans created a habitat for these birds, and are now removing that human-constructed habitat. In response to this problem, artificial chimney swift towers have been constructed over the last few decades. OWU Alumni Dick Tuttle has spent years documenting the many chimney swifts in Delaware, and his experience suggests that a swift tower on OWU’s campus, near Stuyvesant Hall, would be a prime location for the birds. We have visited the site with Peter Schantz who sees no practical problems with the proposed location. Tuttle has tentatively agreed to fund the construction of the tower with a gift to OWU. The typical tower, about 5’ x 5’ and 20’ to 30’ tall, can accommodate around 100 birds. The swift tower will attract student attention: swifts entering the tower at dusk are an impressive sight. For students (and prospective students) pursuing biology, environmental science, and environmental studies the towers will be of much interest. Importantly, for the typical student (or prospective student) the towers will be an intriguing addition to OWU’s campus, signaling OWU’s commitment to the environment while promoting interest in the natural world. The tower, which will have information about chimney swifts and the function of the tower, will serve as an important point of interest on the residential side of campus.

Key Components

Planning for the tower is and will continue to be a collaboration between students, faculty, and alumni. Plans have been developed over several years by students (Caitlyn Buzza ’12, Alex Johnson ’16, and Ashley Tims ’17) working in collaboration with OWU Alumni Dick Tuttle (’73) and faculty members Dustin Reichard (Zoology, ornithology), John Krygier (Geography & Environmental Studies, sustainability), and Kristina Bogdanov (Art, ceramics). Tuttle, Reichard, Bogdanov, and Krygier will work with mason John Kuhn on design details and construction of the tower.

1. The tower will meet the standards set by Paul D. Kyle in his book Chimney Swift Towers: New Habitat for America’s Mysterious Birds, A Construction Guide (Texas A&M University Press, 2005). These guidelines have been used for many successful towers. John Kuhn, our contractor, is an experienced mason who has also taught masonry courses. He should be able to integrate OWU students in the building project if appropriate.

2. Chimney swifts are of immense value to their immediate environment: they are disinterested in humans and are neither aggressive nor dangerous. They consume an immense amount of flying insects, including mosquitos. Thus they serve an important public health role. A functioning chimney swift tower will significantly reduce the number of mosquitos on campus (as they will most likely fly back and forth from the tower to the Olentangy River).

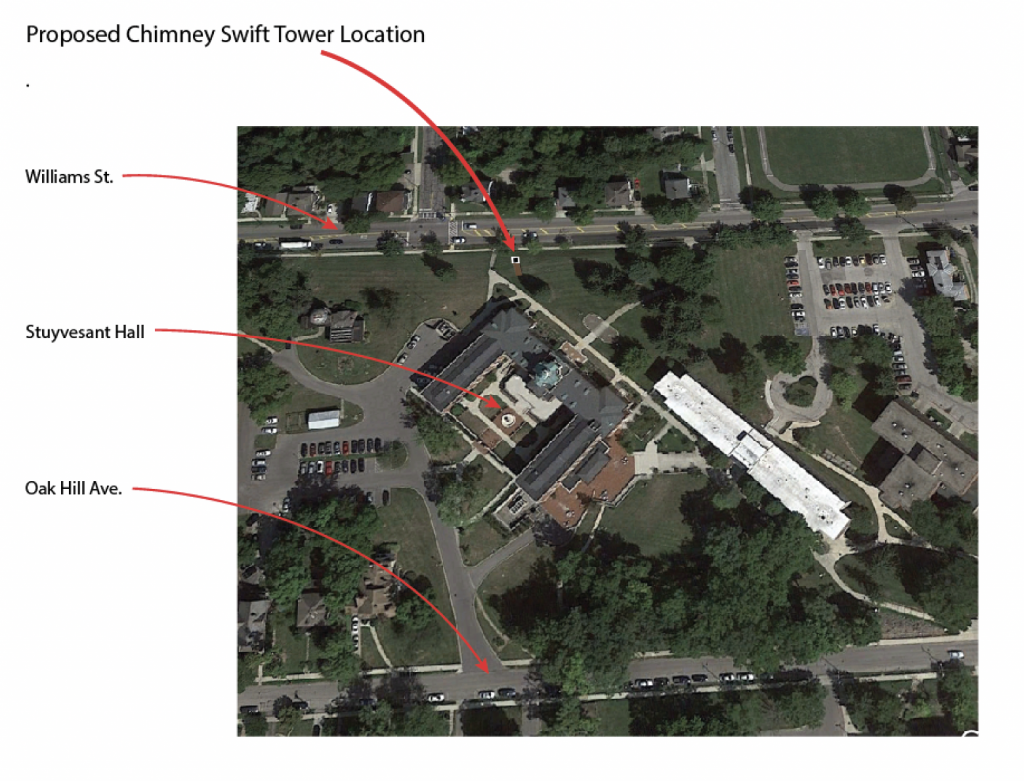

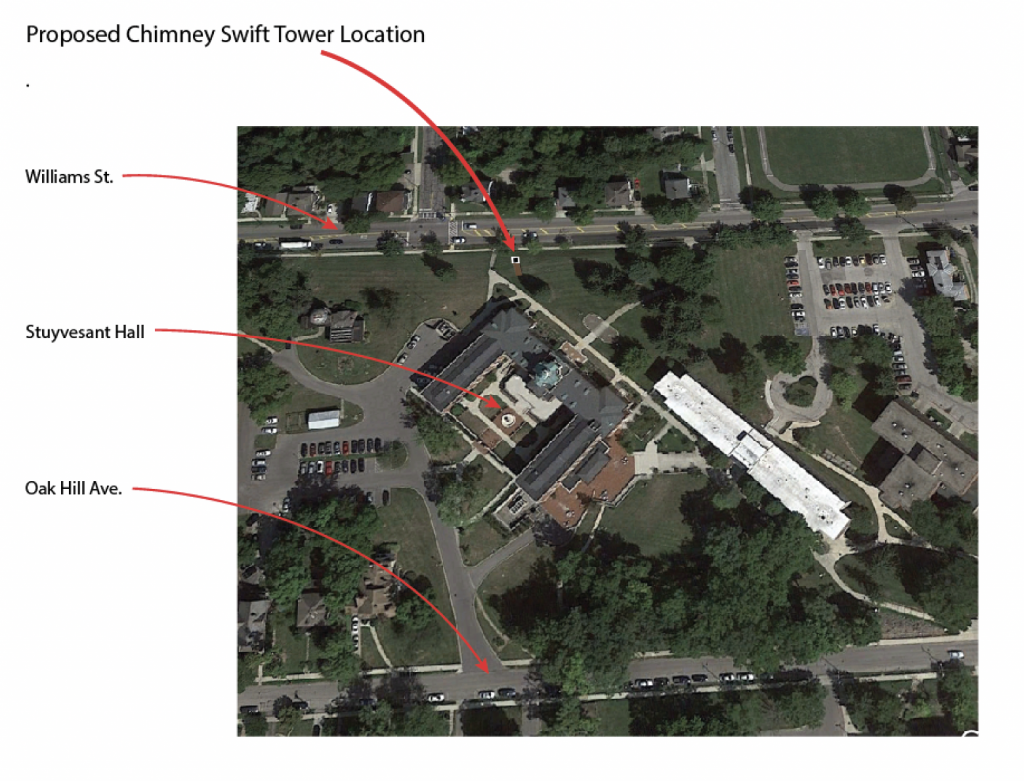

3. The tower will be located to the north-east of Stuyvesant Hall, near the top of the hill that slopes down to William St. This is a good location for the chimney swifts (high, open) but also for observing birds from the residential halls, the newly renovated terrace in front of Stuyvesant Hall, and William St. Peter Schantz has recommended this location. (see below)

Map of location for proposed chimney swift tower.

4. The tower will serve specific courses on campus, and associated faculty and students. In particular, Dr. Dustin Reichard and his ZOOL 341: Ornithology course. See Dr. Reichard’s letter of support. (See Appendix 1).

5. The tower project is representative of student theory-into-practice projects on and around campus, focused on environment and sustainability. For prospective students, the project provides a tangible example of theory-into-practice and campus/community collaboration. The tower project serves as an example of and inspiration for the kind of projects students in the Environment and Sustainability Program (Environmental Studies and Environmental Science) have undertaken in courses such as John Krygier’s GEOG 360: Environmental Geography and GEOG 499: Sustainability Practicum, as well as independent studies and SIP funded projects.

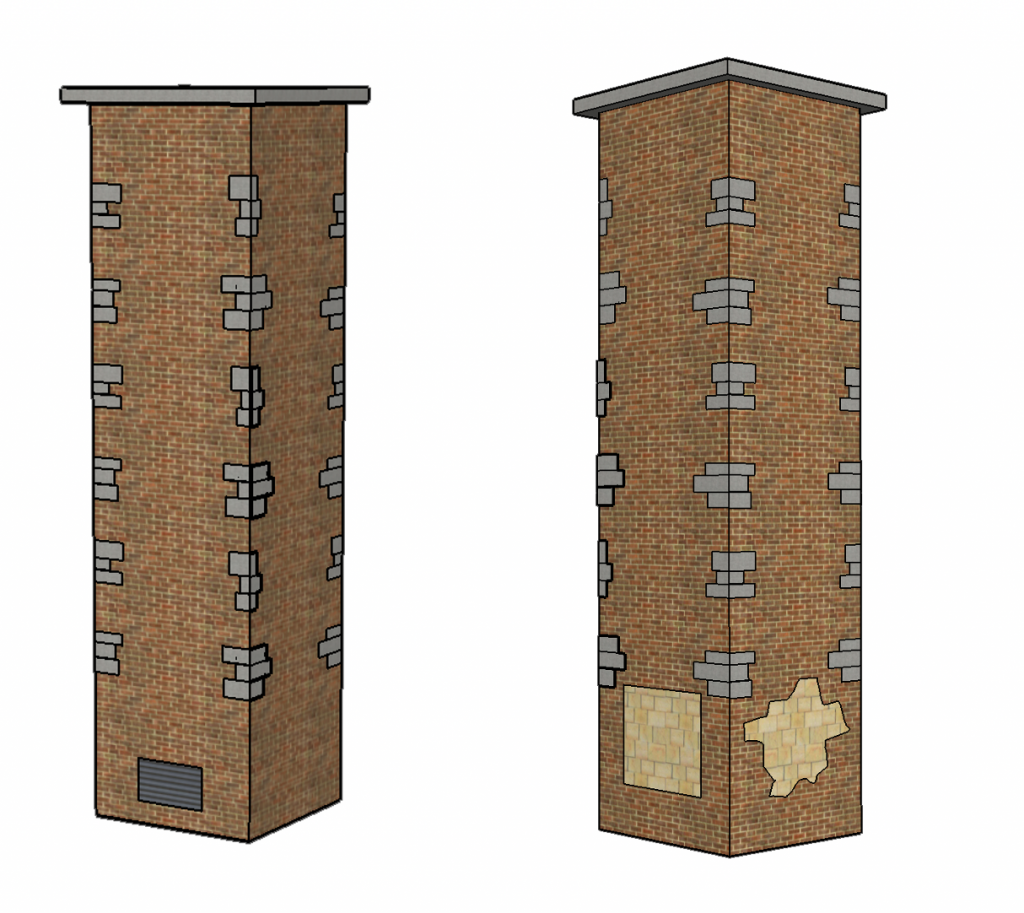

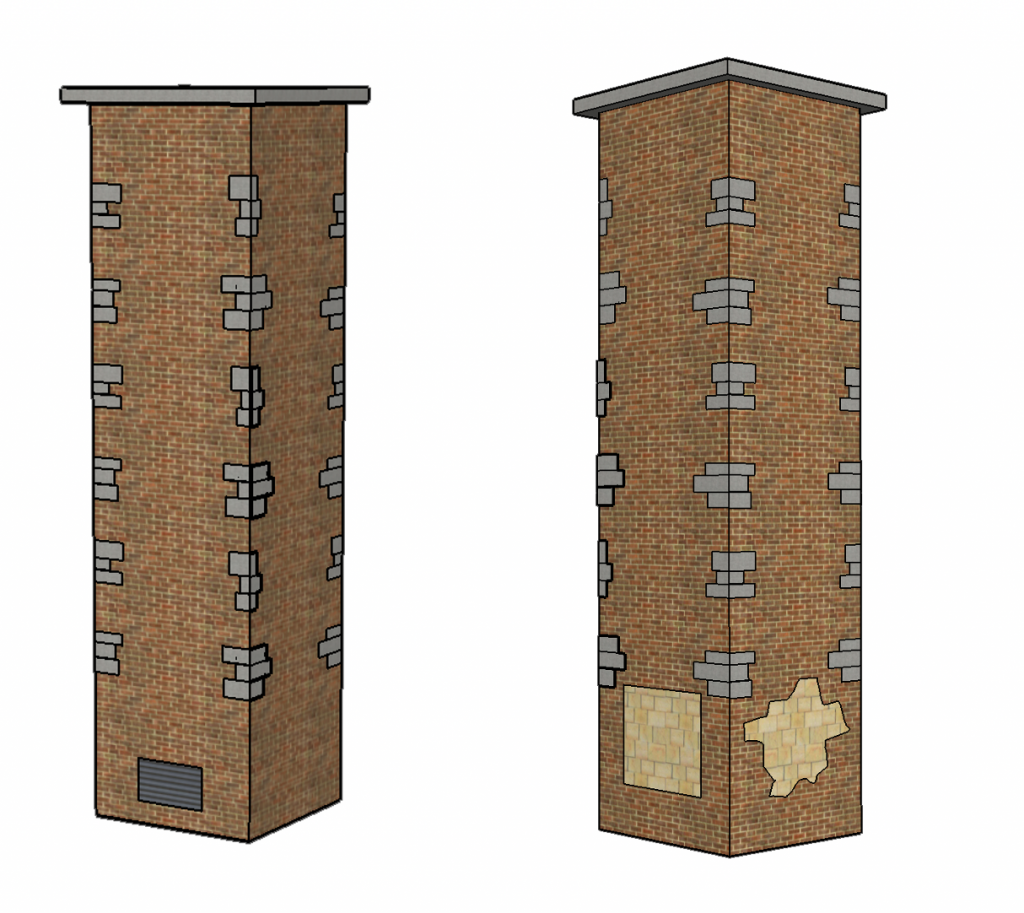

6. The tower will be attractive, fitting into the aesthetic of OWU’s campus while serving as a landmark and destination for students (and prospective students). The preliminary proposal includes brick construction with stone accents using recycled bricks and stone from campus, to match the materials used in Stuyvesant Hall. (see below)

Draft design of proposed chimney swift tower (access hatch, left, tile inserts, right)

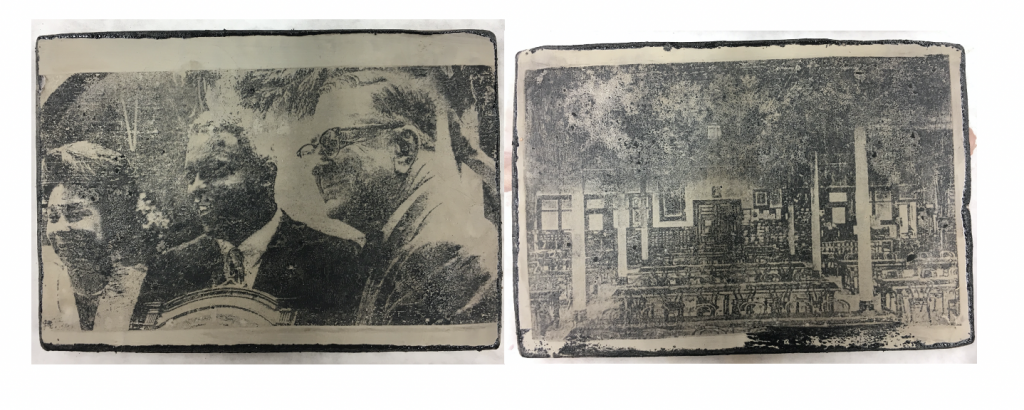

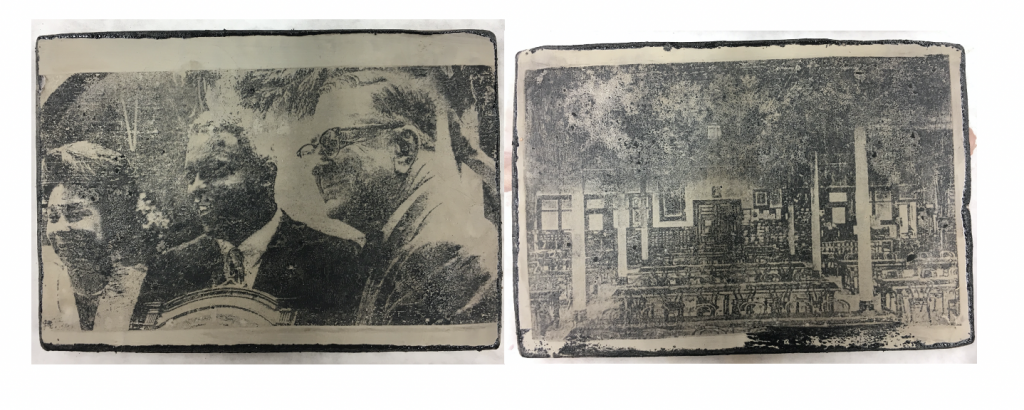

7. The tower will also be tastefully distinctive, with Ohio Wesleyan-themed ceramic artwork near the base. Dr. Kristina Bogdanov (Art, ceramics) has agreed to assist with removable (or permanent) panels at the base of the tower. The primary medium will be tiles, created from recycled clay and dyes. Building on a project started by former OWU biology and art major Ashley Tims (’17), Bogdanov and students will create tiles with permanent images, such as historical OWU photographs (see below). In addition, tiles will be created that depict the leaves of local, native trees and plants, common birds and animals, insects, bees, and other natural features of the campus area. These OWU inspired tiles can be changed out or added to over time. The tiles can be used in activities by admissions (with prospective students) as well as part of orientation for new students, as a way of relating the history and environment of our campus. We also propose a mosaic tile description of the tower, chimney swifts, and illustrations of how the towers work. Thus un-guided visitors can learn what the tower is about and how it works.

Photograph transfer tiles for base of proposed chimney swift tower.

Appendix 1: Letter of faculty support from Dr. Dustin Reichard (Zoology) & Dr. John Krygier (Geology & Geography, Environment & Sustainability)

To: OWU University Advancement & Administration

From: Dustin Reichard (Zoology), John Krygier (ENVS, Geography)

Re: Chimney Swift Tower on OWU Campus

We are writing to convey our strong support for the installation of a chimney swift tower on the OWU campus. Chimney swifts are migratory songbirds that spend their summers breeding in eastern North America and their winters in western South America. Over the past few decades, chimney swifts have been experiencing a steady decline in population size. A major cause of their decline has been the loss of nesting and roosting habitat as homeowners have transitioned away from brick chimneys and either capped or removed chimneys that are no longer in use. The installation of chimney swift towers is one method for mitigating this decline. Delaware is the summer home of a sizable population of breeding chimney swifts that have been monitored for many years by Dick Tuttle, a committed conservationist from the local community that has offered a generous gift in support of this project.

The addition of a chimney swift tower to the OWU campus will provide numerous benefits to the campus community with relatively limited investment from OWU faculty and staff. From a pedagogical perspective, the tower will provide ample opportunities for students to collect and analyze data of swift roosting, migration, and breeding biology. These opportunities will be utilized by students in Ornithology (ZOOL 341), which is taught every spring, and Organisms and Their Environment (BIOL 122), which is taught every semester. Many of our zoology students are interested in careers related to conservation, and the accessibility of a swift tower on campus would allow them to develop skills in population monitoring while working with an at-risk species.

Additionally, chimney swifts are aerial insectivores that will contribute to the management of aerial insects, such as mosquitoes, which are a nuisance and can carry disease. This issue is particularly relevant given the recent expansion of the Zika virus to the southern United States, and the increased likelihood of more tropical parasites in the future as a result of climate change. The swifts also undertake a tremendous migration to the tropics each winter, which makes the bird an excellent international ambassador as OWU seeks to attract a larger number of international students. Finally, observing the birds enter the tower each evening to roost is an amazing natural spectacle that will undoubtedly thrill members of the community for years to come.

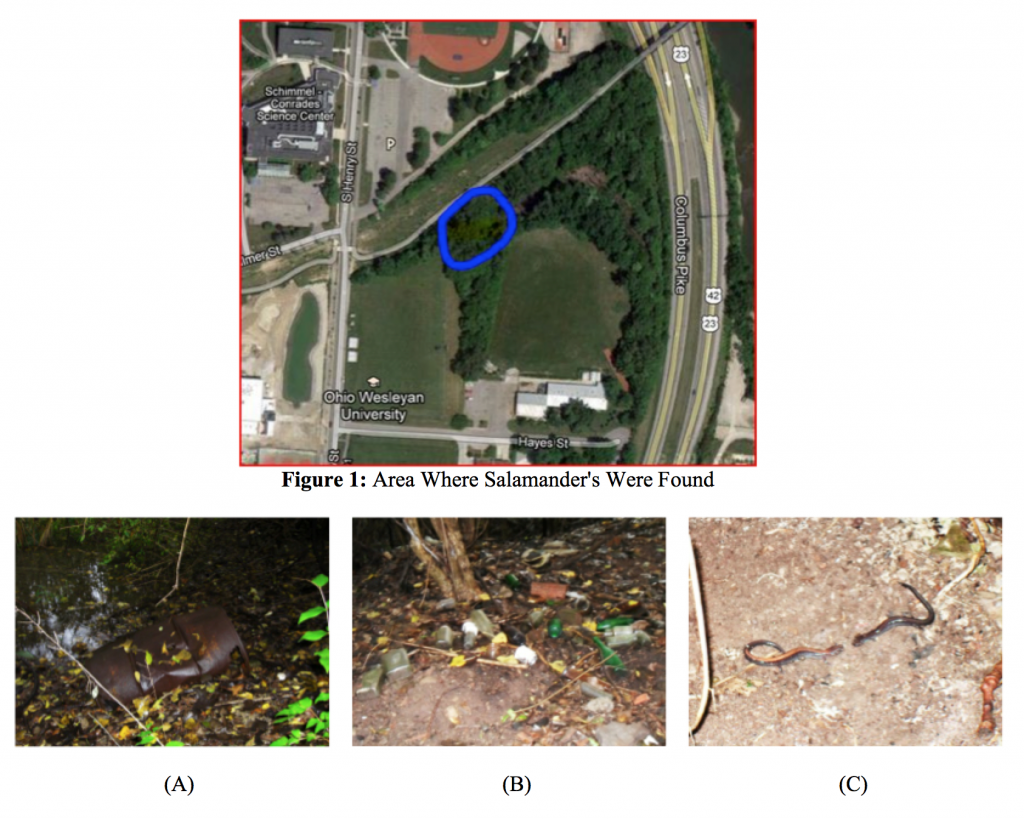

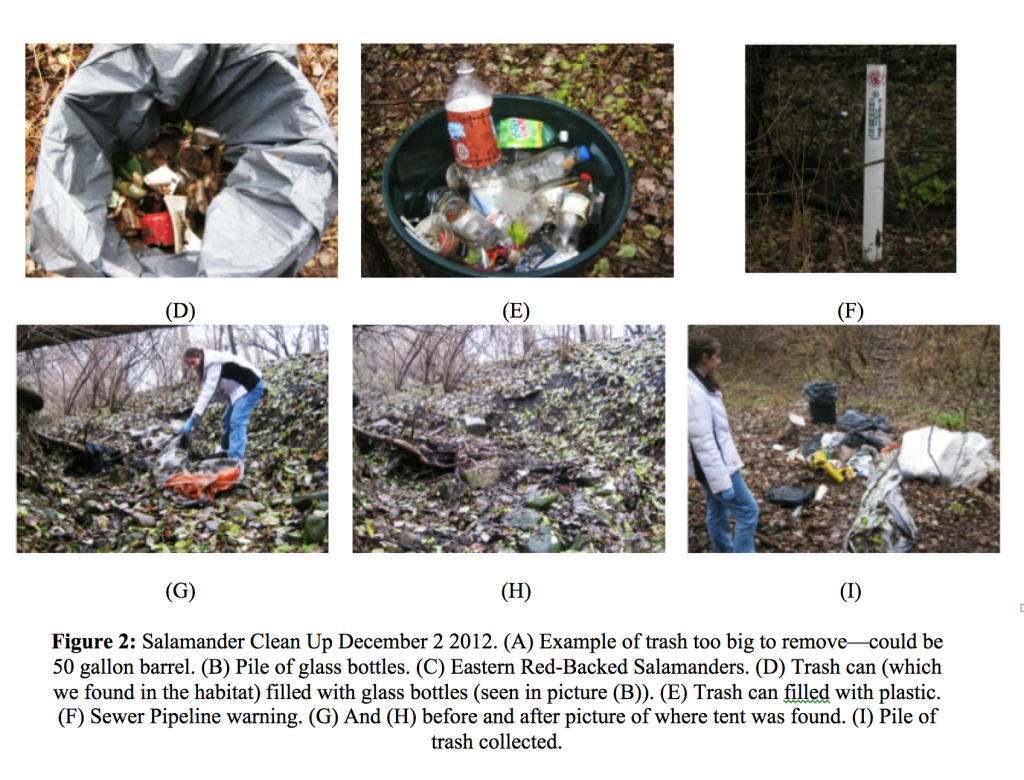

This proposal for chimney swift towers grew out of efforts to enhance habitats for birds, insects, and animals on and around the OWU campus. Work on this project over the past year or two has entailed determining viable locations for the tower, generating plans and designs, all done in consultation with Buildings and Grounds (for advice and input). Additional related campus projects include birdhouses, bat houses, and bee hotels. The development of such habitats on campus is one component of our proposed campus sustainability plan.

Please contact us with any additional questions, and let us know how we can proceed on this important opportunity.

Dustin Reichard

John Krygier