House Wren/Carolina Chickadee house installed on April 16, 2014 during a student event sponsored by the Landscape Course Connection. It now contains a Carolina Chickadee nest.

Jayne Ackerman (OWU ’15, jjackerm@owu.edu), Blake Fajack (OWU OWU ’16, zbfajack@owu.edu) & Dick Tuttle (OWU ’73, ohtres@cs.com)

Delaware County, Ohio, home of Ohio Wesleyan, is one of the fastest growing areas in the state [1]. As the county grows, the amount of wildlife habitat is drastically decreased through fragmentation and other anthropogenic interferences. In order to mitigate the loss of habitat for wildlife we have began enhancing wildlife habitat across OWU’s campus.

A few species were selected in order to jump start OWU’s involvement in rehabilitating habitat area within Delaware. Bats, birds, squirrels, and solitary bees are all common area natives and were targeted to boost ecosystem productivity due to their ecological importance [2][3][4].

Methods and Results

Our original goal for the project was to build and place bat boxes on campus since bats are in danger from habitat loss and important for pest control [19, 2]. We expanded the project to include bird houses and bee hotels because of their ecological usefulness for seed (birds [17]) and pollen (bees [20, 21]) dispersal [3]. OWU Alumnus Dick Tuttle joined our project, suggesting we build carolina wren nesting boxes and expand the project to include squirrel dens. Squirrels are important for tree growth and forest succession [4].

Dick Tuttle guided us on the construction of the bird houses and locations to hang them. We summarized our proposed work in a proposal and contacted OWU’s Buildings and Grounds (B&G) to get formal approval for the project [5]. Our proposal included general ecological support for the habitat enhancements, plans for the shelters (sources in references section at [6][7][8][9][17]), installation procedure [10][11][17], maintenance advice [12][13][17], and location suggestions.

The squirrel dens were dropped from the project because, given their size (and the need for three adjacent boxes) there was a lack of suitable locations for them [17]. The other dwellings remained on the list as we looked forward to the building process. Carlyle Ackerman (Jayne’s father) was the lead carpenter and designer of the bat boxes and a key collaborator in the project.

Bat box construction, October 2014.

Two bat boxes were put together with the help of Mr. Ackerman [18]. This was one of the most time consuming aspects of the project.

When B&G accepted our proposal we contacted the moderators of the Small Living Units (SLUs) on campus, suggesting the SLUs would be a good location for the shelters. Several SLUs came forward: the Tree House, the Interfaith House, and the Citizens of the World House. It was decided that the bird houses would be placed at the Interfaith House and Citizens of the World House, and the bat boxes would be placed at the Tree House. Bee hotels would be hung up along the bike path outside of the Science Center and various other locations.

Simple Bee Hotel Construction: reused plastic soda bottles with tops removed (above).

Fill with cut pieces of dried bamboo (above) and place in bottles (below), packed (Fall 2014) for installation in Spring of 2015.

An event was scheduled [14] to help build additional shelters and spread awareness in hopes of interesting campus groups to maintain and develop the shelters in the long term.

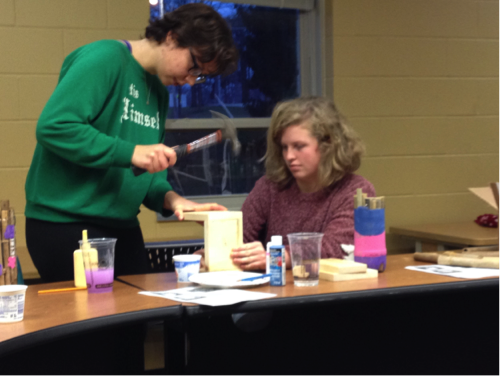

Building Carolina Wren boxes, November 2014.

The event required us to collect necessary materials, tools, and also promotion for the event with social media postings. We also presented our work in class [22]. Emily Webb, Ellen Hughes, and Cindy Hastings attended the event. At the event we built 7 bee hotels, and Dick Tuttle assisted us in building 5 bird houses.

The final step of actually mounting the shelters was planned to happen in January 2015. Fall projects, like ours, suffer from the inevitable descent into winter. Both Jayne, Blake and Dick Tuttle committed to finishing the dwellings and installing them in the spring of 2015.

Spring 2015 Efforts and Results

Bird feeders outside of the Schimmel Conrades Science Center (above) and Chapplear Drama Center(below). The feeders are currently maintained by OWU Alumni Dick Tuttle and we would like a student organization to take over maintenance of the feeders.

The feeder stands that hold four feeders are checked daily. Oil sunflower seeds are added to the milk carton feeders. The water bottle feeders are loaded with thistle seed for American Goldfinches and House Finches.

One bottle feeder at each stand has seed ports where American Goldfinches can feed while hanging up-side-down, a maneuver that House Finches cannot duplicate.

A small suet feeder hangs from one of the milk cartons and it is used by woodpeckers, nuthatches and chickadees.

A new hopper feeder was installed on April 27. It can go days before feed is depleted. Three ears of corn are attempts to attract Blue Jays, a species not yet seen at the feeder stations. Crows and grackles might also feed on the corn. Also, on each end of the hopper are compartments designed to hold suet and/or slices of bread, etc.

Carolina Wren boxes painted (above) by residents of the SLUs where the boxes will be mounted, March 2015.

April 25, 2015: Box 3 (above) at the student observatory has one egg in its moss nest.

April 25, 2015: Box 4 between the Hamilton-Williams Center and the

Alumni Center. It contains three Carolina Chickadee eggs.

Future of the Project

General Maintenance of Dwellings

- All of the wildlife dwellings need general monitoring to keep an eye out for wear and tear.

- Occasional repairs or remounting may be needed depending on the amount of weathering.

Bee Hotel Maintenance

- The simple design of the bee hotels may not allow them to last very long but they can be easily made and replaced.

Bat Box Maintenance

- Bat boxes are self sufficient but sometimes pests like wasps will take over while bats are not using the boxes. These types of problems may require professional services.

- If the bat boxes are not being used after 3 summers they will need relocated.

- The SLUs that are hosting bat boxes will be expected to keep these maintenance requirements in mind.

Carolina Wren Nestbox Maintenance

- Nestboxes will need cleaned once a year in the summer after birds have left the house.

- The SLUs that are hosting nestboxes will be responsible for the cleaning.

Other wildlife home ideas

- Larger bee hotels, lady bug homes, general bug hotels [15]

- Bee hives

- Squirrel dens [4, 8, 11]

- Other bird houses: bluebird nest boxes or chimney swift tower [17]

- Wildlife brush piles [16]

- Bird of prey nesting platform

Recommendations

- Getting the B&G proposal done as soon as possible is the number one thing to do when working on this type of project as they took a while to get back to us. Research is very important in case B&G has any questions or your project needs more scientific support.

- Have a back-up plan. Original plans may not work out, so be sure to always have an alternative. Don’t be afraid if it is not as good as a place to put the shelter. Even the most poorly placed shelters will help B&G get used to the idea of having them around.

- Try to start a native garden near the shelters, or mount the shelters in close proximity to a native plant garden. This helps attract the targeted wildlife to the shelter.

References

[1] Delaware County: http://www.co.delaware.oh.us [2] Why Bats are Important: http://www.batconservation.org/bat-houses [3] Why Bees are Important: http://www.esa.org/ecoservices/comm/body.comm.fact.poll.html [4] Why Squirrels are Important: http://www.rossoscoiattolo.eu/en/role-ecosystem [5] B&G Proposal: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B6uLhpiaH654OGoxV1dtMjFsZ3M/view?usp=sharing [6] Bee Hotel Plans: http://www.opalexplorenature.org/sites/default/files/7/file/How-to-make-a-bee-hotel.pdf [7] Carolina Wren Nest Box Plans: http://www.wholehomenews.com/blog/Carolina-Wren-Nest-Box/239 [8] Squirrel Den Plans: http://www.helpingwildlife.org/images/squirrelnestbox.pdf [9] Bat Box Plans: http://www.nwf.org/How-to-Help/Garden-for-Wildlife/Gardening-Tips/Build-a-Bat-House.aspx [10] Bat Box Installation: http://www.batcon.org/pdfs/bathouses/InstallingYourBatHousebuilding.pdf [11] Squirrel Den Installation: http://northernredsquirrels.org.uk/Red-Squirrel-Nesting-Box-Info.pdf [12] Bat House Maintenance: http://bathouse.com/bat-house-maintenance [13] Bird House Maintenance: http://www.birdhouses101.com/Care-Maintenance-Birdhouses.asp [14] Facebook Event: http://www.birdhouses101.com/Care-Maintenance-Birdhouses.asp [15] Bug Hotels: http://gardentherapy.ca/build-a-bug-hotel/ [16] Rabbit Brush Piles: http://dnr.wi.gov/files/PDF/pubs/wm/WM0221.pdf [17] Dick Tuttle [18] Carlyle Ackerman [19] Sheffield, S.R., Shaw, J.H., Heidt, G.A., McClenaghan, L.R. 1992. Guidelines for the protection of bat roosts. Journal of Mammalogy 73: 707-710. [20] MacIvor, J.S., Cabral, J.M., Packer, L. 2014. Pollen specialization by solitary bees in an urban landscape. Urban Ecosystems, 17: 139-147. [21] Danforth, B. Bees. Current Biology, 17,5: R156-R161. [22] Wildlife Home Presentation: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B6uLhpiaH654ay1jYzRYSWRPT0k/view?usp=sharing