OWU’s Salamander Swamp

Fall 2013

Tiffany Green, Amy Downing, John Krygier, Sean Kinghorn, Thomas Wolber, Milagros Green, Sara Starzyx

Summary

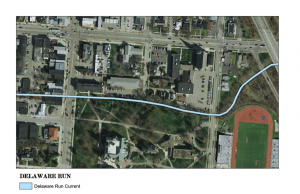

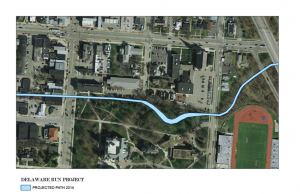

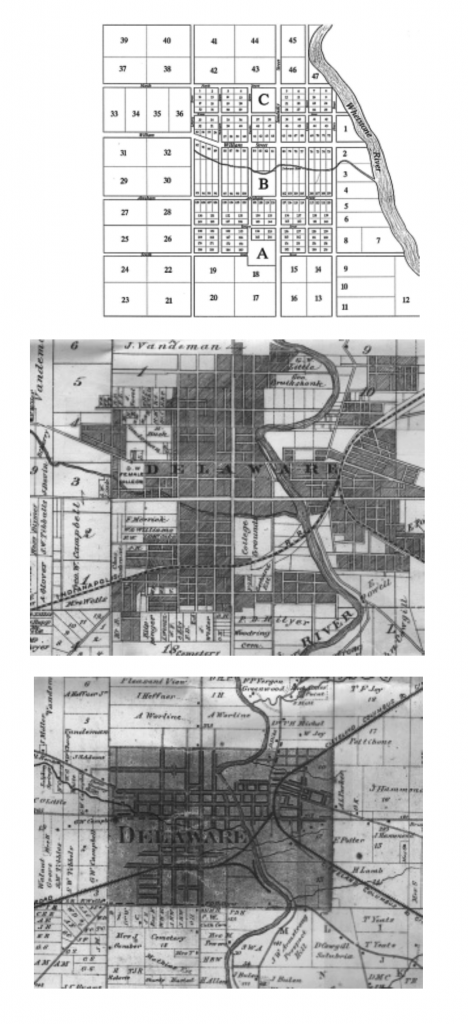

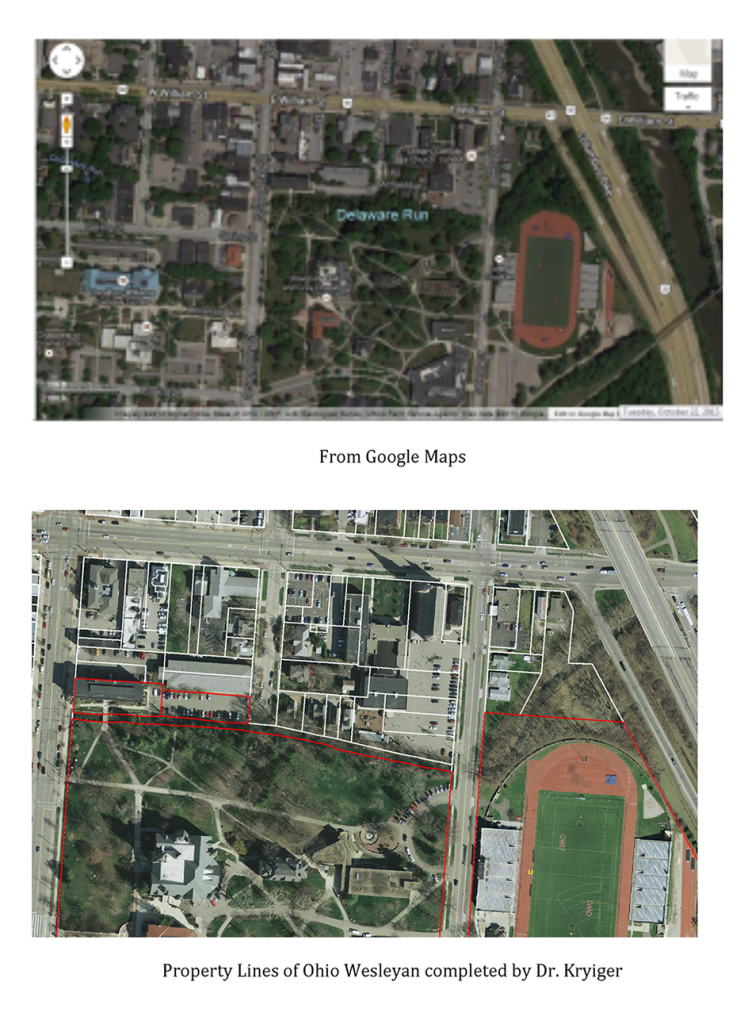

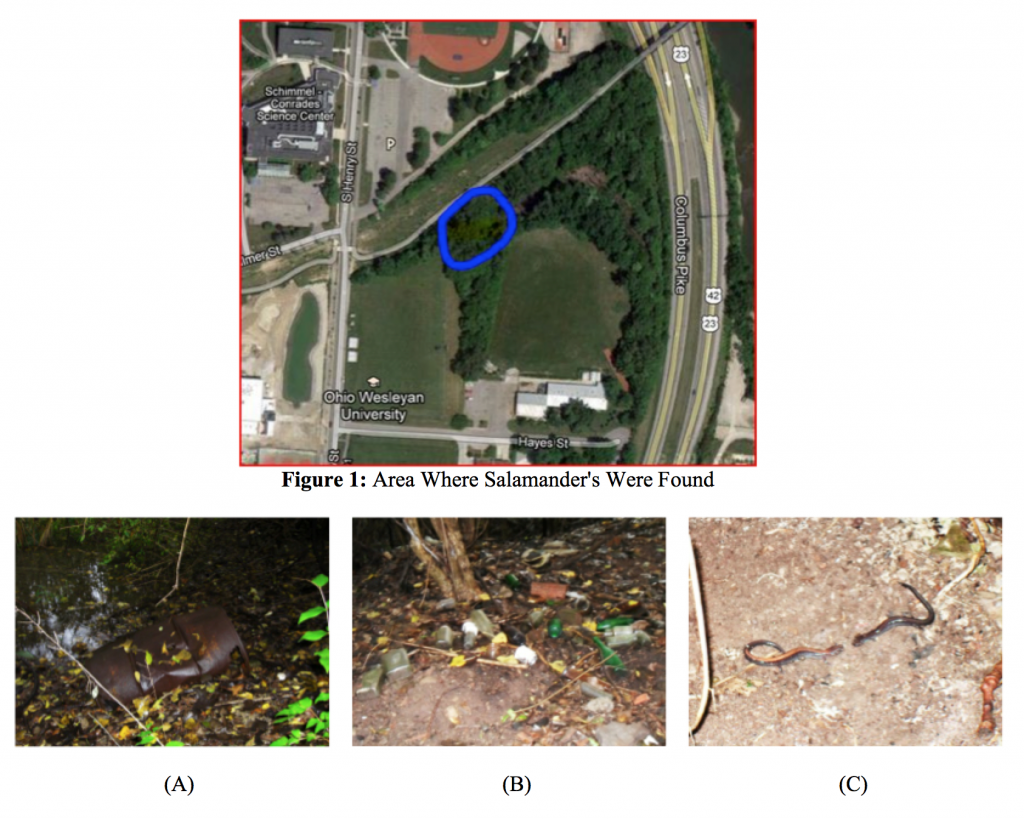

Wildlife can thrive in even the most marginal of habitats. A small wetlands area exists at the edge of Ohio Wesleyan’s campus, pinched between the recreational trail, US Highway 23, and OWU Athletic fields. This habitat, artificially created by the significant landscape modifications in the area over the past 100+ years, supports salamanders and other wildlife, despite poor water quality, noise, half-buried waste from an old Ohio Wesleyan dump, and garbage. This project builds on an earlier project that removed garbage from the area and provided a basic assessment of the location and animal species present. Our goal for the current project is to consider the development of the area as an outdoor classroom and research location. To this end, we need to complete a more thorough assessment of animal and plants in the area, test the water (and potentially soil) and consider steps (short and long term) to enhance the habitat. Habitat enhancements may include the addition of salamander-friendly wood “houses,” invasive plant species removal, improved (but ecologically friendly) access for class and researcher access, remediation of water pollution sources, remediation of litter sources, noise reduction, etc.

Methods and Results: Fall 2012 Clean-up

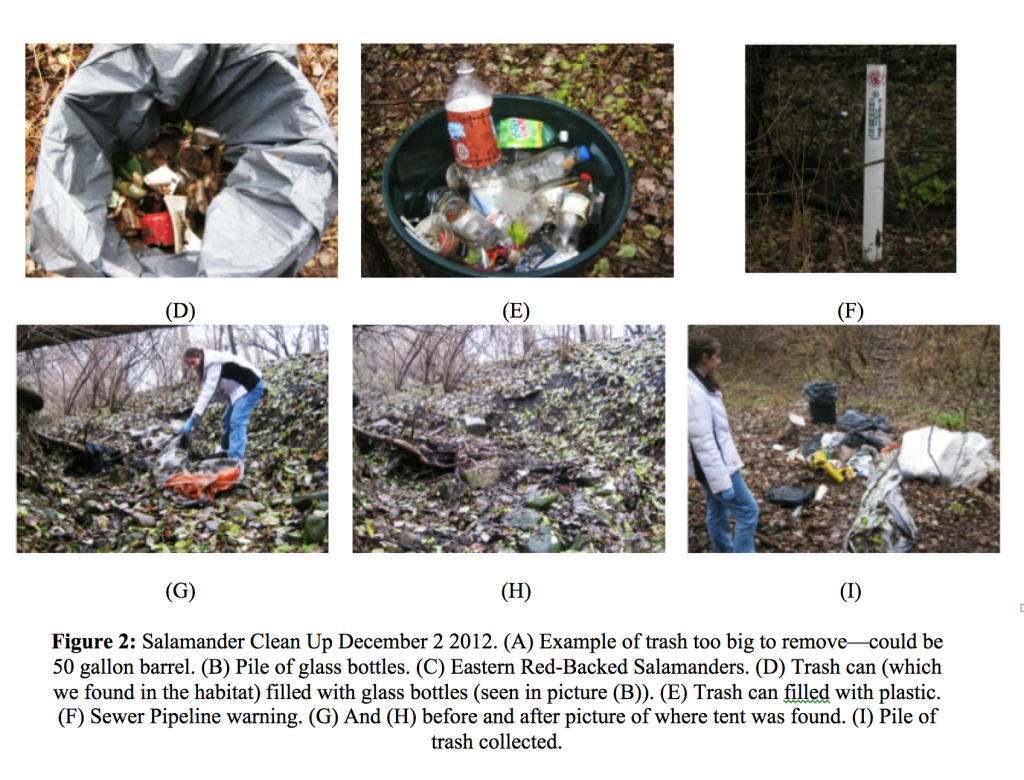

The original project involved a quick assessment of the habitat, to see if any salamanders could be found, prior to a cleanup of garbage in the area. We weren’t expecting to find salamanders; therefore it came as a shock when three Eastern Red-Backed Salamanders were found, almost immediately, under rotting trees and rocks near the water. Photos were taken and later the species was identified by comparing the images to ones shown on the internet. While finding the salamanders was positive, the habitat itself was a mess. The area was filled with trash; pillows, a shower curtain, parts of a car, a tent, bottles, ceramics, cooking utensils etc. Some of the older trash dates from the time that the area was used as a dump by Ohio Wesleyan, including half-buried barrels, vehicle parts, etc. Newer trash has descended into the area from the recreation trail, US 315, and the athletic field to the south of the habitat.

Sustainability Coordinator Sean Kinghorn helped organize a day (Fall 2012) where volunteers could help remove trash from the habitat. Sean provided trash bags, gloves, and lawn shears as well as a place to dispose of the trash. The date was set in December, because by then all salamanders would be hibernating and so we would be less likely to disturb them. Trash was removed in and around the area where the three salamanders were found. All except for those pieces that were too big, or too heavy to lift. This ended up being not such a bad thing since animals seemed to be using the car parts, tires etc. as their homes. In order to clear out the area, a rudimentary path was created by utilizing fallen logs and cutting away the underbrush. By using the path to get down the steep incline, all trash from the area was cleared, and ended up filling ten trash bags. We recycled what we could. Clearing out the trash is only the first step to saving the salamanders and their habitat; there is much left that needs to be done.

Recommendations: Fall 2012

- Complete a more assessment of animal and plants in the habitat. Initiate a salamander census as the first step in assessing numbers over time. Assess salamander migration into and out of the area, if possible, and obstacles to this migration. Collaborate with OWU faculty and students who may be interested in using this habitat for research.

- Evaluate the water in the habitat, including sources. Test the water to evaluate any problematic pollutants.

- Evaluate the soil in the habitat.

- Evaluate noise in the habitat (primarily US 315)

- Create salamander friendly “houses” in the habitat

- Evaluate the removal of invasive species that adversely affect the area as a habitat for salamanders and other native animal species.

- Evaluate access to the area for class and student research purposes.

- Organize another trash clean up late 2013.

- Develop a long-term plan for habitat enhancement and use as an Ohio Wesleyan ecological research location.

Methods and Results: Fall 2013 Removal of Invasive Plant Species

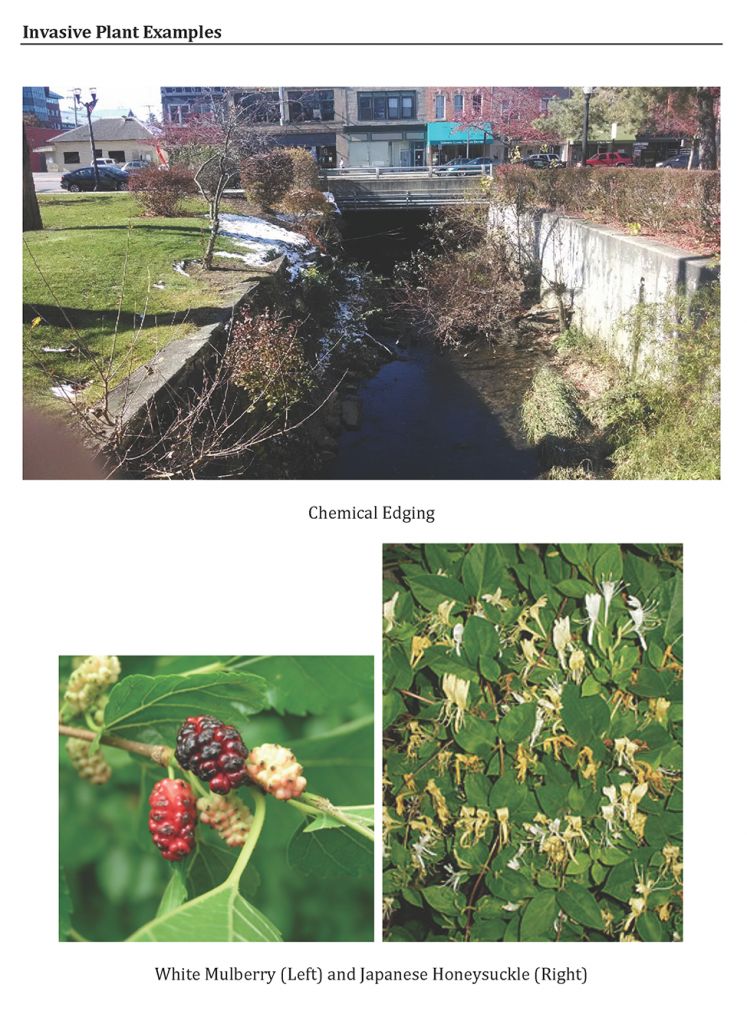

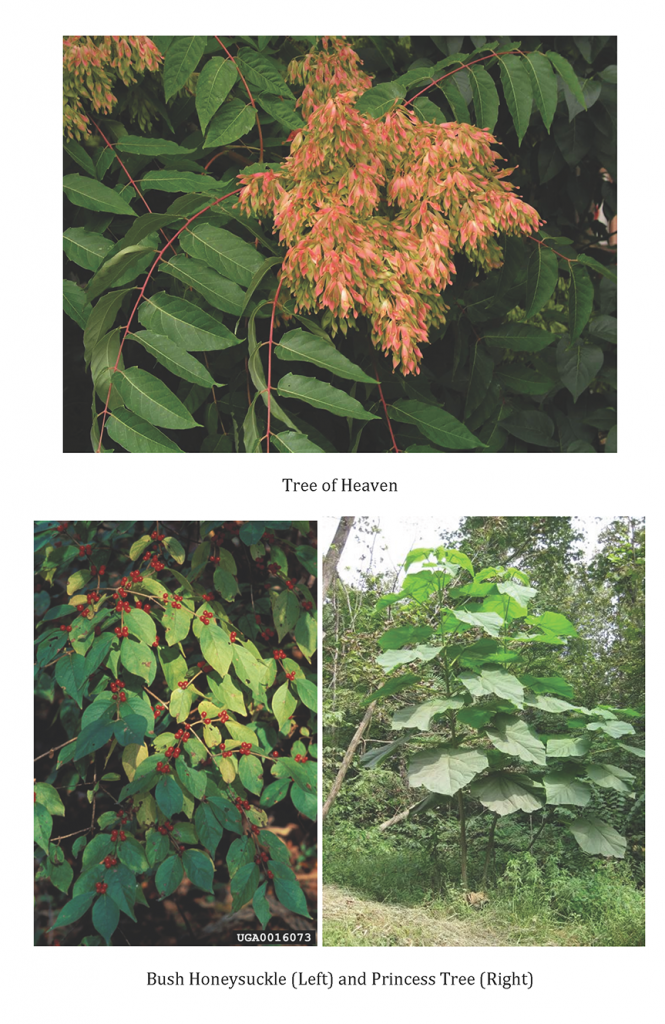

Amphibians require aquatic and terrestrial habitats to complete their lifecycles, and preservation of both habitats is necessary for maintaining a steady population. A study done in 2004 showed that spotted salamanders, Jefferson’s salamander complex and smallmouth salamanders were positively associated with the amount of forest within a core zone (Porej 2004). Some invasive species thin out forests and this could have a negative impact on the salamander population found at the edge of OWU’s campus. With the help of Ohio Wesleyan student Thomas Bain, the invasive plant species most abundant within the wetland were identified. These two invasive species were amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii) and garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata). Almost all plants within the wetland being studied were invasive. Because of this, it was thought that before removal of all invasive plant species could take place, an assessment of the impact this might have needed to be taken into account first.

Successful eradication efforts have generally benefited biological diversity. However, there is also evidence that, without sufficient planning, successful eradication can have unwanted and unexpected impacts on native species and ecosystems. Sometimes the eradication of an invasive species can hurt a native species. This happens if the native species has begun to use the invasive as a nesting habitat (as with the willow flycatcher and exotic saltcedar). But even when this is not the case, sometimes invaded areas are no longer able to support the growth of native plant species (Zavaleta 2001). This may be true with both amur honeysuckle and garlic mustard.

Amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii) tends to shade out native vegetation, particularly in the understory, they deplete soil moisture, and there have been studies that have shown that these plants increase pH levels in the soil (Hicks 2004 and Exotic honeysuckles 2013). Garlic mustard produces allelochemicals which suppress mycorrhizal fungi that most plants require for optimum growth (Garlic mustard 2013 and Alliaria petiolata 2013). So even with the removal of all the amur honeysuckle and garlic mustard from the area, native plant species may need additional help to reestablish themselves, since the soil might no longer be suitable for their growth.

These two invasive species are detrimental to salamander health. A study done in 2011 found that Amur honeysuckle affected the microclimate (temperature and humidity at ground level) of forest’s understory. Mean daily temperatures were lower in invaded plots compared to those not overrun with Amur honeysuckle. This was correlated with a decline in amphibian species richness and evenness in invaded plots (Watling 2011). Another study focusing on garlic mustard impacts was done in 2009. It was found that this plant was correlated with a diminish in prey resources of the woodland salamander (Maerz 2009).

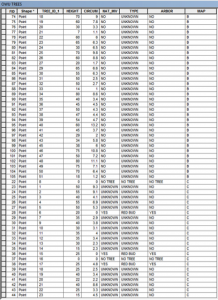

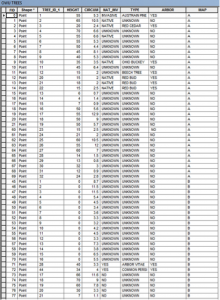

Four plots of land within the wetland were marked off using flags. These plots were each 10 meters by 10 meters, and each pair was chosen according to how similar they were to each other. From each pair, one would have the invasive plants removed, while the other remained how it was found; acting as the control. After being marked off, the plots were carefully searched through for salamanders. Salamanders were found under rock and leaves. After finding the salamander, the disturbed rocks and leaves were placed back as close to the original location as possible.

| Plot Number | Number of Salamanders Found |

| 1 | 3 |

| 2 | 4 |

| 3 | 2 |

| 4 | 4 |

Table 1. The number of salamanders found in each plot before invasive species were removed.

After the salamanders were found and recorded, the invasive species, amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii) and garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), were removed from plots 2 and 4. Garlic mustard, small plants of 12 to 36 inches in height was removed by pulling the plants out by the base of the stem. Amur honeysuckle was more challenging. To remove this plant, shovels were used to dig beneath the thickest part of the root. With the soft shifting soil, amur honeysuckle could then be pulled out of the ground without much strength needed.

The following day a follow up count of the salamanders was recorded from all plots (using the same methods from the previous day).

| Plot Number | Number of Salamanders Found |

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 2 |

| 4 | 0 |

Table 2. The number of salamanders found in each plot after invasive species were removed from plots 2 and 4.

The data collected shows that the plots removed of invasive species had a substantial decreased in number of salamanders found. It seems that the removal of invasive species did cause the salamanders to move from the area disturbed, but in order to have significant results this count must be redone in the spring to see if the salamander’s numbers increase in the areas without any invasive plant species, or if they stay mostly the same.

References

John C. Maerz, Victoria A. Nuzzo, Bernd Blossey. 2009. Declines in woodland salamander abundance associated with non-native earthworm and plant invasions. Conservation Biology 23: 975-981.

James I. Watling, Caleb R. Hickman, John L. Orrock. 2011. Invasive shrub alters native forest amphibian communities. Conservation Biology 144: 2597-2601.

Erika S. Zavaleta, Richard J. Hobbs, Harold A. Mooney. 2001. Viewing invasive species removal in a whole-ecosystem context. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 16: 454-459.

“Exotic honeysuckles (Lonicera tartarica, L. morrowii, L. x bella).” Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. (2013) Web. 6 Nov. 2013.

Sara L. Hicks. 2004. The effects of invasive species on soil biogeochemistry. Hampshire College.

“Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata).” Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. (2013) Web. 6 Nov. 2013.

“Alliaria petiolata.” Wikipedia. (2013) Web. 6 Nov. 2013.

Deni Porej, Mick Micacchion, Thomas E. Hetherington. 2004. “Core terrestrial habitat for conservation of local populations of salamanders and wood frogs in agricultural landscapes.” Conservation Biology 120: 399-409.